Biodiversity Flashcards

Diversity (types)

Genetic diversity

Species diversity

Ecological diversity

Functional diversity

Biodiversity movement

Movement addressing environmental concerns in relation to politics, biology, and ethics

Ecological diversity

Concept relating to variability of trophic levels, life cycles, and biological resources

Biodiversity

Term analogous to biological diversity; popularized in the 80s by E.O. Wilson

Biological diversity

Concept referring to the variety and abundance of species in a spatial unit

Taxonomic distinctness

Measure of diversity similar to Simpson’s index

Diversity measures

Measure taking into account richness and abundance

Richness

Simply the number of species in a spatial unit

Evenness

Measure of differences in abundance between species

Diversity index

A single statistic conveying information on richness and abundance

Heterogeneity

Concept incorporating both richness and evenness

a-diversity

Diversity within a defined spatial area

b-diversity (concept)

The extent to which the diversity of two or more spatial units differ; Concept conceived by Whittaker (1960) originally to measure diversity changes between samples along transects, but commonly used for changes along other spatial arrangements and over time.

Dominance

The extent to which one or a few species are primarily conform a community

Abundance (and evenness) visualization

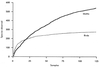

1) Histogram: abundance (y axis) against ranked species (x axis)

2) Rank/abundance plot (aka Whittaker): line graph of relative abundance (in log10 scale) against ranked species; the steeper the curve, the lower the evenness of the assemblage

3) k-dominance plot: line graph of cumulative relative abundance (y) against ranked species (x); The more elevated the line is from the x axis, the less diverse diverse the assemblage

4) Abundance/biomass comparison (ABC plot): Same as k-dominance, but cumulative relative biomass also plotted

5) Fisher plot: Number of species (y) plotted against number of individuals (x); looks like a very lef-skewed histogram

6) Preston plot: Number of species (y) plotted against number of individuals in a log2 scale arranged in “octaves” (x); can use other log base; looks like a bell-shape (i.e., log normal model)

Pattern vs process

Pattern refers to the way a system behaves

Process refers to the reasons why a system behaves in a particular way

Biodiversity measurement (assumptions)

- All species are equal

- All individuals are equal

- Abundance is expressed in comparable units

Biodiversity (nature as a science)

Biodiversity is a comparative science by nature

Community

Group of organisms in a defined area that interact among themselves

Guild

A group of organisms using the same resources

Assemblage

Group of organisms in a communiy that share a certain phylogeny

Local guild

Group of organisms using the same resources and co-ocurring in an area

Ensemble

Group of organisms sharing geographic distribution, resources, and phylogeny

Self-similarity

A pattern of diversity maintained across different spatial scales

Geographic boundary of a community

Set arbitrarily by te researcher

Statistical vs biological models

Statistical models aim to describe observed patterns, while bioloical models aim to explain those patterns

Logarithmic series model

Statistical model proposed by Fisher (1940s) to describe the relationship between number of species and number of individuals in those species;

αx, αx2/2, αx3/3…αx/n

αx is the number of species predicted to have one individual, and so on

the paremeter α is a good index of diversity

Log normal model

Statistical model proposed by Preston (1940s); Describes species abundance against species ranks (log2) resulting in classes called octaves. Can use other bases (e.g., 3 or 10).

Most large assemblages follow this distribution.

Incroporates γ as an additional parameter when a number of individuals curve is superimposed on the number of species curve.

The distribution is canonical when γ=1, in which case the mode of the individuals curve coincides with the upper tail of the species curve.

Log normal: Statistical explanation for its commonness in real data

Log normal distribution might be common as a result of the central limit theorem, wich states that when the amount of a variable is determined by a large number of factors, random variation in the factors will result in a normal distribution.

Additional support: more specious assemblages tend to be canonicl compared to less specious

Log normal: Biological explanation for its commonness in real data

Log normal distribution can be a consequence of random niche division/invasion.

Log normal distribution: Veil line

Truncation point of a log normal curve resulting as a consequence of difficulty sampling the less abundant species.

Note that veiled distributions are more difficult to fit.

Log normal (fitting and nature of data)

Technically, a log normal distribution should only be fitted to continuous abundance data such as biodiversity, but large discrete datasets work fine because they often act as continuous

Poisson log normal

A variation of the log normal distribution that assumes discrete abundance classes.

Uses the Poisson parameter λ, which is also a robust index of diversity.

Log normal: visual method for seeing fit of data

Plotting cumulative frequency of species (y) against log2 rank classes (x) should look like a straight line

Log normal: implication of departure

Departure of an assemblage from a log normal distribution is often used as a sign of environmental disturbance (though this is a challenged view)

Overlapping distributions (explain)

Data are often described by more than one distribution model

Overlapping of log series and log normal distribution

Potentially explained by a difference between permanent species (log normal distribution) and occasional species (log series distribution); when plotted together, the result is a left-skewed distribution.

Other statistical models besides log series and log normal

Negative binomial; Zipf-Mandelbrot

Fitting a model to data

Goodness of fit tests (usually X2) are used to evaluate the relationship between observed and expected frequencies.

X2 = [(observed - expeted)2/expected]

A P<0.05 means the model does not describe the observed pattern.

Goodnes of fit test for small datasets

Kolmogorov-Smirnov goodness of fit test may be applied to small datasets and can also be used to compare two datasets

Niche appointment models

Noche appintmt models are based on the assumption that a community has a property called niche space that is divided in a certain way among species.

Different biological models vary in the way they propose niche fragmentation/filling occurs.

Niche filling

An alternative mehcanism to niche fragmentation in which additional niche space is accomodated (e.g., newly formed habitats like island and lakes).

Deterministic vs stochastic statistical diversity models

Deterministic models assume tat a set number of individuals, N, will be distributed among species, S, in a particular way.

Stochastic models establish that replicated communities will vary in their species abundances.

Most statistical models are deterministic, while most biological models are stochastic

Geometric series model

The geometric series is a biological model that assumes dominance-based niche appointment undrer limiting factors, and a relationship between allocated niche and abundance.

Usually observed in data from species-poor and harsh environments.

Broken stick model

Biological model proposed by McArthur (late 1950’s). The model proposes niche division occurs like a stick is simultaniously being divided at random. Imporant in the development of ecological thought but rarely fits empirical data.

Tokeshi’s models

Niche appointment models (biological models) proposed by Tokeshi (90’s). They all assume niche space is occupied by species proportionally to abundance, but propose different mechanisms of niche division.

1) Dominance pre-emption: niche of least abundant species is subdivided

2) Random fracion: niche to be subdivided is selected at random

3) Power fraction: probabiltiy of division is moslty random but slighlty influenced by size

4) McArthur fraction model: probability of division proportional to size

5) Dominance decay: largest niche invariably split

6) Random assortment: No relationship between niche appointment and species abundance

7) Composite: small niches divided randomly and large niches divided following a rule

Caswell’s neutral model

An alternative biological model, proposed by Caswell (late 1970’s). Operates by examining how species abundance would occur in a community if all interactions were removed.

Hubbell’s neutral theory of biodiversity and biogeography

A more ambitious neutral model than Caswell’s. Proposed y Hubbel (2000). In this bioloical model, metacommunities are composed of a set of local communities that are always saturated, so there is no place for new individuals until others die.

The relative abundance of a species in a local community is dictated by its aundance in the metacommunity.

Explains a great number of empirical systems. One complication is that it requires simulations.

Fitting stochastic niche appointment models to empirical data

Communities are repetedly constructed using simulation, which allows to produce confidence limits on expected abundances. If the observed model fits within the confidence intervals, a model is said to fit the data.

Does not work if the variance is greater than that predicted.

Replication of observations in required (increases power) but not necessary (i.e., when detecting community changes over time).

Comparing abundance patterns between communities

The Kolmogorov-Sminrov two-sample test allows to determine whether two communities have the same pattern of abundance.

Criteria for classifying species as rare

1) Relative criteria: Example: species in the first quartile of the distribution are considered rare. This will vary depending on the measure used to quantify abundance (e.g., number of individuals vs biomass).

2) Absolute criteria: Example, all species with only one individual (singletons) are considered rare.

Rarity (mechanistic components)

Rarity occurs as a function of:

geograhpic distribution, habitat specificity, and local population size.

Rarity (definition according to the International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources

Taxa with small populations and restricted geographic areas that are often scattered.

Biggest obstacles for measuring biodiversity

- The variety of species conepts and lack of consensus

- Taxonomic bias

- Sampling issues (rare = lower detectability); sampling scale (spatial and temporal); sampling effort

Morphospecies (aka morphotypes)

Morphospecies are taxa that are distinguishable on a morphological basis, without necessary taxonomic knowledge.

Ways of expressing richness measures

- Numerical (i.e., number of species per abundance or biomass category)

- Species density (number of species per area unit)

- Incidence (number of sample units in which a species is present)

Richness indices

Richness indices attempt to compensate for sampling effects by dividing S by N in some way. Examples include Margalef’s diversity index and Menhinick’s index. These indeces are still influenced by sampling effort.

Methods to estimate true richness from samples

1) Extrapolation

2) Examining shape of species abundane curves

3) Nonparametric estimators (most powerful approach)

Species accumulation curves

Examines the rate at which new species are added by simulating the the samples in a randomized way a certain number of times. Mean and SD are also calculated.

The product is a plot of cumulative numer of species (y) by sampling effort (x).

Species accumulation curves produce total values of richness.

Can be used to 1) compre communities

2) evaluate sample size adequacy.

Species area curves

Similar to species accumulation curves, examines the rate at which new species are added to an inventory, but uses area units instead of sequential sampling. Widely used in botanical surveys.

Rarefaction curves

Rarefaction curves are similar to species accumulation curves, but instead of explaining richness as samples are added, it explains it by examining what pattern would have been produced if sampling effort had been reduced.

Rarefaction curves produce mean values of richness and can be viewed as the statistical product of a species accumulation curve.

Rarefaction curves are mostly used to compare assemblages.

Richness extrapolation (conditions)

To extrapolate richness, sampling needs to:

1) occur in a systematic way as opposed to ad hoc (as needed)

2) occur in a homogenous habitat

Richness extrapolation (types)

Functions of richness extrapolation can be:

1) asymptotic (e.g., negaive exponential, Michaelis-Menten equation)

2) nonasymptotic (e.g., log linear models)

Abundification

A parametric method to estimate the overall species richness in an assemblage or the increase in S expected from additional sampling.

α is estimated from the observed S and N, and used to deduce S given a larger N.

Requires that the data conform to a log series distribution.

Also allows to compare communities with unequal sampling effort.

Log normal: Issues for fitting to data

1) assumes continuous data

2) requires a large sample size (N > 1,000)

3) choosing abundance classes is problematic

4) no method for condifence intervals

5) Poisson log normal is harder to fit

Nonparametric estimators of richness

Not based on any particular species abundance model and therefore avoid issued related to fitting parametric models.

Chao 1

Chao 1 is a nonparametric estimator for absoule richness based on a ratio between singletons and doubletons:

SChao1 = Sobs + (F12/2F2)

- F*1: number of singletons

- F*2: number of doubletons

Chao 1 assumes homogeneity among samples.

Chao 2

Nonparametric estimator of richness. Variation of Chao 1 for presence/absence data:

SChao1 = Sobs + (Q12/2Q2)

- Q*1: species present in only 1 sample

- Q*2: species present in 2 samples

Coverage estimators

Based on the idea that abundant species are likely to be included in any sample and thus provide little information about a community. In constrast, information about rare species is more useful.

Abundance-based coverage estimator (ACE)

A coverage estimator based on species with 1 - 10 individuals.

Incidence-based coverage estimator (ICE)

A coverage estimator based on species found in ≤10 samples.

Other nonparametric estimators

Jacknife 1: uses the numbr of species found that occur one sample.

Jacknife 2: uses the numbr of species found that occur in one and two samples.

Bootstrap estimator: also uses incidence data.

Stopping rule

Stopping rule is an indicator that further sampling is not required.

Two examples of approaches to determine the sampling stopping point:

1) Empirical species accumulation curve crosses curve generated by Michealis-Menten.

2) No singletons are left.

3) Subdivide sample in two (at random) and check that both subsamples follow the same pattern.

4) Estimators become stable and stop rising.

Richness estimators: desirable qualities

1) can use a sample size as small as posible.

2) Accuracy

3) allow an estimation of variance

4) not biased

5) computationally efficient

Species surrogacy tpes

1) Cross-taxon: richness of one taxon used to infer richness of another

2) Within-taxon: familiar or generic richness used as a surrogate for species richness

3) Environmenal: relatonships between environmenal factors and species richness

Heterogeneity measures (categories)

Heterogeneity measures are classified as parametric or nonparametric

α

Parametric measure of the log series model used to fit the distribution; Can be used as a measure of diversity even when the log series model doesn’t fit the data; It is possible to attach confidence intervals; It’s unaffected by sample size.

λ

Parametric measure of the log normal distribution; Calculated as S/σ.

(σ is standard deviation); λ is in itself an effective measure of biodiversity.

Q statistic

Parametric measure that uses the inerquartile slope of a cumulative abundance curve; Not biased by rare or very abundant species; Similar use to α from log series.

Shannon’s diversity index

Nonparametric measure of diversity; Calculated by the equation:

H’ = - Σpi lnpi

where pi is the proportion of individuals in the ith species.

It’s value constrain (1.5. and 3.5) makes it diffcult to interpret; Also, it confounds richness and evenness.

Shannon’s evenness measure

A nonparametric measure of evenness, separate of H that uses the ratio of observed diversity to maximum possible diversity. Symbolized by J’

Heip’s index of evenness

An alternative to J’ (Shannon’s evenness measure) that is less senitive to species richness; Calculated with the formula:

EHeip = (eH’ - 1)/(S - 1)

SHE analysis

Nonparametric diversity measure based on the relationship between species richness, H (Shannon’s index), and eveness; allowing a better interpetation than H.

Graphing SHE can be used to distinguish between broken stick, log series, and log normal as an alternative to using a goodness of fit test.

The Brillourin index

A nonparametric diversity measure similar to H that is appropriate to use when randomness of sample is not achievable (e.g., pitfall traps); Cannot be used with abundance or productivity measures.

Simpson’s index (D)

Nonparametric measure of diversity that uses the proportion of individuals in each species to determine the probability of any two individuals to be drawn from the sample.

Because diversity decreases as D increases, a reciprocal (1 - D or 1/D) is often reported to make things more intuitive.

One of the most robust and meaningful measures of diversityl, but less popular than H.

Simpson’s measure of evenness (E)

A separate measure of evenness from D (which is not strictly one). The reciprocal of D is divided by total number of species:

E1/<em>D</em> = (1/D)/S

Ranges from 0 to 1 and is not sensitive to richness.

McIntosh’s measure of diversity

A nonparametric measure of diversity that uses the Euclidean distance of the assemblage from its origin, reresented as U.

Nee, Harvey, and Cotgreave’s evenness measure

Nonparametric measure of eveness; slope (b) of a rank/abundance plot with log abundance;

Falls between ∞ and 0 (0 is perfect eveness); hard to interpret due to value range.

Smith and Wison’s evenness index

Evar, A nonparametric measure of evenness that measures the variance in species abundance.

Four requirements for a good diversity measure, according to Smith and Wilson

1) indepndent of richness

2) decreases along with abundance of the least abundant species

3) decreases if a rare species is added

4) unaffected by measure units

Taxonomic diversity

Taxonomic diversity is thought to make an assemblage more resilient and diverse. It’s a useful measure in conservation, but can hinder the identification of vulnerable assemblages and is sensitive to sampling effort.

Clark and Warwick’s taxonomic distinctness index

Clark and Warwick’s taxonomic distinctness index describes the average taxonomic distance (measured as a path’s length) between species.

has two forms:

1) Taxonomic diversity Δ: Average path length between two random individuals.

2) Taxonomic distinctness Δ*: Special case of Δ where each individual is drawn from a different species.

Each taxonomic level receives a different weighting.

Can be compared to simulated values and is independent of richness.

Taxonomic distinctivness

Refers to a species of particular conservation importance.

Sample size sensitivity

Sample size sensitivity is a common problem of diversity measurements that complicates comparison of assemblages. One solution is sample standarization across sites.

Functional diversity

Can be measured by branch length from dendrograms constructed from a number of traits;

A powerful technique for evaluating the functional consequences of extinction.

The positive relationship between species richness and ecosystem function is often attributed to a greater number of functional groups.

Body size and diversity

Avrage body size, togeter with guild identity allows to infer about abundance.

Sampling for biodiversity (issues)

1) Sample size and sampling effort: The number of species and therefore diversity will increase with number of samples. Thus, sample size must be standarized or adjusted for. Ideally, the number of samples should be so to achieve an asympote when plotted with a measure of diversity or eveness.

2) Nonrandomness: Sampling is assumed to be random, but in reality might not be (e.g., environmental heterogeneity, individual behavior).

Replication/pseudoreplication

True replicates must be spatially independent.

Methodological edge effects

When sampling inefficiency results in concluding one or more species is absent or rare (e.g., sampling methods, sampling time)

Measuring abundance: Modular units

Sampling units regarded as different individuals from one larger clonal individual (e.g., fungi, trees, corals). The use of modular units is justified by sub-individuals acting as true individuals ecologically.

Measuring abundance: Biomass as an abundance measure

Biomass can be a good surrogate of abundance, and provides information on resource use.

It can also reduce numerical differences between species that vary in their abundances by orders of magnitude.

Measuring abundance: Cover area

Cover area can be used as a surrogate of abudnance but is problematic, as organisms can overlap.

Measuring abundance: Frequency or incidence

The number of sampling units in which a species occurs. It can be an useful measure for richness.

However, the abundance of widespread species can be underestimated.

Comparison of communities: Species abundance distributions

Species abundance patterns can be compared between communities through hypothesis testing (e.g., Kolmogorov-Smirnov test) and slope comparison.

Comparison of communities: Rarefaction

Method to measure species richness. A good way of comparing two communities with confidence intervals.

Allows the adjustment of sample size between communties by calculating what richness would be if less samples would have been taken.

Assumes that sampling was truly random.

Note the shape of rarefaction curve is expected to vary depending on the species abundance distribution type.

Comparison of communities: Statistical tests

because thr Shannon, Simpson, and other statistics are often normally distributed, they can be compared with t tests and ANOVA.

Comparison of communities: Jackknifing

Becaue jackknifing is a nonparametric method, one of its biggest advantages is that it makes no assumption about the underlying distribution of data.

1) diversity (i.e., and index) is estimated for all samples tgether: St

2) diversity is recalculated n times leaving out one sample at a time: St-i

3) pseudovalues are then calculated for each sample

4) jackknifed estimate is the mean of all pseudovalues

5) SE used to perform t tests

Comparison of communities: Bootstrapping

Bootstrapping is a method similar to jackknifing (and considered an improvement). The original data set is repeatedly sampled to produce many combinations of observations and these are used to calculate a standard error.

Comparison of communities: Null models

A fairly recent approach to compare a community in question against a series of random draws from a regional pool. Can also be used to test if differences in diversity are an artifact of sampling.

Environmental assessment

Environmental assessment evaluates the status of potentially impacted assemblages against a benchmark expectation.

1) Species/abundance distributions: undisturbed assemblaes usually follow a log normal pattern.

2) ABC curves: Placement of individual/biomass curves used to infer on disturbances. W statistic (a measure linking biomass and abundace) can be compared with a sttistical test.

3) Richness: Number of species simply used to infer on disturbance

4) Taxonomic distinctness: Δ+ used to infer on ecosystem function.

5) Indices of biotic integrity (IBI’s): integrate a number of metrics; requires extensive background information; not intended for measures of diversity.

Turnover

The number of species eliminated and replaced per unit time.

Term is also used sometimes for spatial changes, though β is more appropriate in that situation.

Levels of diversity

Inventory diversity:

α diversity: the diversity of a set of samples form one spatial unit

γ diversity: the diversity of a landscape

ε diversity: the diversity of a geographic region

Differentiation diversity:

pattern diversity: variation in diversity between samples from a site

β diversity: the difference in diversity between two spatial units or points in time

𝛿 diversity: change in diversity betwee units of γ (landscapes)

Note: no concensus on how to define a landscape or geographic region.

β-diversity and area sampled

Contrary to α, β-diversity decreases as the area sampled increases.

Levels of richness

According to Gray (2000):

Scale

point species richness: richness of a sampling unit

sample species richness: richness from a number of samples from one site

large area richness: richness from an area including a variety of habbitats

biogeographic province species richness: richness of a biogeograpic province

Independent of scale

habitat species richness: richness in a habitat

assemblage species richness: richness of an assemblage

β-diversity formula

, where ST is the species richness of the landscape;

- Sj* is the species richness of the assemblage j;

- qj* is the proportional weight of assemblage j based on its sample size.

Measuring β-diversity (trhee main approaches)

1) Difference between 2 areas of α-diversity in respect to γ-diversity (where γ-div is measured as richness); e.g., Whittaker and Lande

2) Similarity/dissimilarity between 2 areas of α-diversity(e.g., Jaccard and Bray-Curtis coefficients)

3) Measuring turnover in terms of the slope in a species-area realtionship

Whittaker’s β<span>W</span>

One of the simplest and most effective measures of β-diversity;

βW = S/(mean α)

or

Dβ = ST/(mean Sj) in Lande;s notation

Values range from 1 to 2; often reported as β - 1 to set the range from 0 to 1

Harrison’s modifications of βW

1) βH1 = {[(S/mean α) - 1]/(N - 1)} * 100

sets range from 0 - 100

2) βH2 = {[(S/αmax) - 1]/(N - 1)} * 100

αmax is the maximum within-taxon richness per sample;

Often used to compare turnover of different taxa

Other measures of β-diversity

1) Cody’s measure βC: Focuses on lost vs gaines species

2) Routledge’s measures βR (takes overlapping distributions into consideration)

βI (based on information theory)

βE (the exponential form of βI)

3) Wilson’s and Smida’s measure βT (focuses on loss and gain like βC, but uses average sample richnes like βW).

Wilson and Shmida’s criteria for a good β-diversity measure

1) Number of community changes

2) Additivity

3) Independece from α diversity

4) Independence from excessive sampling

βW considered the best measure under these criteria

Complementarity

Describes the difference between sites in terms of species they support; used for conservation;

Very similar to β-diversity; The more complementary two sites

Complementarity measures

Complementarity measres combine three variables: a (species present in both samples), b (species present in sample 1), c (species present in sample 2).

Maczewski-Steinhaus measure

Complementarity measure calculated as:

CMS = 1 - a/(a+b+c)

Jaccard’s measure

Complementarity measure calculated as:

CJ = a/(a+b+c)

Sorensen’s measure

Complementarity measure calculated as:

CS = 2a/(2a+2b+2c)

Lennon’s measure

Complementarity measure that focuses on differences in composition; calculated as:

βsim = 1 - [a/a+min(b,c)]

smallest values of b and c are used to avois inflating value

CN = 2jN/(Na + Nb);

a version of Sorensen that takes abundance into account

A ccomplementarity measure taking abundance into account; calculated as:

CN = 2jN/(Na + Nb)

Regarded as the best complementarity measure.

Morisita-Horn

Popular complementarity measure that is very sensitive to the abundance of the most abundant species. A way of dealing with that is square transforming the raw data.

Estimating the true number of shared species

V is an index to estimate complementarity that focuses on the rare species providing more information than abundant ones.

Cluster analysis

A method to compare betwee communties in terms of β-dibversity; Works by constructing dendrograms based on site similarities, where distance is measured. Boostrap values can be added.

Includes dentrograms and ordination.

ANOSIM

Analysis of similarities; a one-way nonparametric test using permutations to test a null hypothesis;

Comparisons are made among localities with a number of replicates.

Null expectation contrasting

A method to compare communities in terms of β-dibersity.

An observed pattern of β-biodiversity is contrasted against a null expectation.

β measure distribution comparison

Whittaker’s multiplicative law

Gamma diversity is a product of Alpha and Betta diversity

Phytosociology

The science that aims to clasify plant communities into fixed units

Niche

An n-dimensional hypervolume composed by environmental and resource characteristics that a species requires to persist (Hutchinson 1959).

Assembly rule (Diamond 1975)

A restricted species combination to which competitive ineractions can lead.