Session 3 Flashcards

(59 cards)

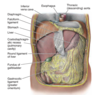

Describe the structure and layers of the abdominal wall

- Altough continuous, the abdominal wall is subdivided into the anterior wall, right and left lateral walls and the posterior wall. The boundary between the anterior and the lateral walls is indefinite therefore the term anterolateral abdominal wall is used.

- The anteriolateral abdominal wall is composed of skin, subcutaneous tissue (superficial fascia/fat), muscles and their aponeuroses, deep fascia, extraperitoneal fat and parietal peritoneum.

- The anterolateral abdominal wall is bounded superiorly the cartilages of the 7th-10th ribs and the xiphoid process of the sternum, and inferiorly by the inguinal ligament and the superior margins of the anterolateral aspects of the pelvic girdle (iliac crests, pubic crests and pubic symphysis).

- During a general physical examination, the abdominal wall is inspected and the underlying organs are palpated.

- As access to the abdominal cavity requires surgical incision, knowledge of the composition of the abdominal wall is necessary before carrying out any physical or surgical procedure.

What does the Superficial Fascia consist of?

The superficial fascia consists of fatty connective tissue. The composition of this depends on its location:

- Above the umbilicus: a single sheet of connective tissue. This is continuous with the superficial fascia in other regions of the body.

- Below the umbilicus: it is divided into 2 layers; the fatty superficial layer (Camper’s fascia) and the membranous deep layer (Scarpa’s fascia). Superficial vessels and nerves run between these two layers of fascia

Describe the major landmarks of the abdominal wall part 1: umbilicus, epigastric fossa, linea alba, pubic crest and symphysis, inguinal groove, semilunar lines (linea semilunaris)

- Umbilicus: at spinal level L3 / dermatome T10

- Epigastric Fossa (pit of the stomach): slight depression in the epigastric region, just inferior to the xiphoid process. Particularly noticeable when a person is in the supine position (lying down, face up) because the abdominal organs spread out. Heartburn is commonly felt at this site.

- Linea Alba: aponeuroses of abdominal muscles, separating the left and right rectus abdominis. Visible in lean individuals because of the vertical skin groove superficial to it. If the linea alba is lax, when the rectus abdominis contract the muscles spread apart. This is called divarication of recti

- Pubic Crest and Symphysis: the upper margins of the pubic boens and the cartilaginous joint that unite them. Can be felt at the inferior edge of the linea alba.

- Inguinal groove: a skin crease that is parallel and just inferior to the inguinal ligament (runs between ASIS and pubic tubercle). Marks the division between the abdominal wall and the thigh.

- Semilunar Lines (Linea Semilunaris): slightly curved, tendinous line on either side of the rectus abdominis – running from the 9th rib to pubic tubercle. It is the lateral border of the rectus abdominus

What are the tendinous intersections of the rectus abdominis? What is the arcuate line?

- Tendinous Intersections of Rectus Abdominis: clearly visible in persons with well-developed rectus muscles. The interdigitating bellies of the serratus anterior and external oblique muscles are also visible.

- Arcuate Line (aka Douglas’ line): where the fibrous sheath stops (inferior limit of the posterior layer of the rectus sheath), 1/3 of the way from the umbilicus to the pubic crest.

What are the 5 muscles of the abdominal wall?

There are 5 bilaterally paired muscles (3 flat and 2 vertical) in the antero-lateral wall.

The flat muscles end anteriorly in a strong aponeurosis (flattened tendons) each of which interlaces in the midline at the linea alba. The flat muscles are External Oblique, Internal Oblique and Transversus Abdominis

With their opposite counterparts they form the rectus sheath which contains the two vertical muscles and neurovascular structures

Describe the 3 pairs of flat muscles individually

External Oblique (origin, insertion)

- External surfaces of the 5th to 12th ribs

- Linea alba, pubic tubercle and anterior half of iliac crest

Internal Oblique

- Thoracolumbar fascia, anterior 2/3ds of iliac crest and connective tissue deep to lateral third of inguinal ligament

- Inferior borders of the10th to 12th ribs, linea alba and pectin pubis via conjoint tendon

Transversus Abdominis

- Internal surfaces of 7th to 12th costal cartilages, thoracolumbar fascia, iliac crest and connect tissue deep to lateral third of inguinal ligament

- Linea alba with aponeuroses of internal oblique, pubic crest and pectin pubis via conjoint tendon

What do the flat muscles do?

- The 3 flat muscles’ fibres have varying orientations with the fibres of the obliques running diagonally and perpendicular to each other, and the fibres of the transversus running transversely.

- The three flat muscles are continued anteriorly and medially as strong, sheet-like aponeuroses. Between the mid-clavicular line and the midline, the aponeuroses form the tough, aponeutoric, tendinous rectus sheath that encloses the Rectus Abdominis

- The aponeuroses then interweave with their fellow of the opposite side, forming the linea alba which extends from the xiphoid process to the pubic symphysis. The interweaving is not only between right and left sides but also between intermediate and deep layers.

- The flat muscles are important in flexing, twisting and lateral flexion of the trunk. Their fibres run in differing directions and cross each other, strengthening the abdominal wall and decreasing the risk of herniaton

- Their contraction increases intra-abdominal pressure during activities such as lifting, coughing, defecation, urination, parturition (giving birth).

Describe the Rectus Sheath

- The Rectus Sheath is formed by the aponeuroses of the three flat muscles, and encloses the rectus abdominus and pyramidalis muscles. It has an anterior and posterior wall for most of its length:

- The Anterior wall is formed by the aponeuroses of the external oblique, and of half of the internal oblique

- The Posterior wall is formed by the aponeuroses of half the internal oblique and of the transversus abdominus.

- Approximately midway between the umbilicus and the pubic symphysis, all of the aponeuroses move to the anterior wall of the rectus sheath. At this point, there is no posterior wall to the sheath; the rectus abdominus is in direct contact with the transversalis fascia.

- The area of transition between having a posterior wall, and no posterior wall is known as the arcuate line.

Describe the vertical muscles

The two vertical muscles of the anterolateral abdominal wall are contained within the rectus sheath, the large Rectus Abdominis and small Pyramidalis

- Rectus Abdominis is a long paired muscle, found either side of the midline in the abdominal wall. It is split into two by the linea alba. The lateral border of the two muscles create a surface marking called the linea semilunaris. At several places, fibrous strips, known as tendinous intersections, intersect the muscle. The tendinous intersections and the linea alba give rise to the six pack seen in individuals with low body fat.

- As well as assisting the flat muscles in compressing the abdominal viscera, the rectus abdominis also stabilises the pelvis during walking, and depresses the ribs.

- The pyamidalis is a small triangle-shaped muscle, found superficially to the rectus abdominis. It is located inferiorly with its base on the pubis bone and the apex of the triangle attached to the linea alba. It acts to tense the linea alba.

What to consider when doing a surgical incision?

- The location of the incision depends on the type of surgical operation, the location of abdominal viscera (organs), avoidance of nerves (particularly motor nerves), maintenance of blood supply, etc.

- E.g. severance of a motor nerve(s) will lead to muscle paralysis, thereby causing abdominal wall weakness.

- When design an incision, we want one that we can close and provide long-lasting strength, thus minimising the incidence of incisional herniae. Improper healing of a surgical incision or scar may become a site where herniation of the abdominal viscera can occur through the abdominal wall.

- If we try to sew muscle together, the sutures will ‘cut out’ (think sewing butter)

- Consider direction of muscle fibres (you want to split the muscle fibres rather than cut them)

Describe common vertical incisions

- Median/Midline: an incision that is made through the linea alba. It can be extended the whole length of the abdomen, by curving around the umbilicus. The linea alba is poroly vascularised, so blood loss is minimal and major nerves are avoided. All can be used in any procedure that requires access to the abdominal cavity.

- Paramedian: similar to the median incision but is performed laterally to the linea alba, providing access to more lateral structures (kidney, spleen and adrenals) This method ligates (ties up) the blood and nerve supply to muscles medial to the incision, resulting in their atrophy

Describe common transverse incisions

- Transverse: this incision is made just inferior and laterally to the umbilicus. This is a commonly used procedure as it causes least damage to the nerve supply to the abdominal muscles and heals well. The incised rectus abdominus heals producing a new tendinous intersection. It is used in operations on the colon, duodenum and pancreas. Surgeons suture the external oblique aponeuroses together to provide a strong closure

- Suprapubic (Pfannenstiel): incision is made about 5cm superior to the pubis symphysis. They are used when access to the pelvic organs is needed. When performing this incision, care must be taken not to perforate the bladder (especially if it is not catheterised) as the fascia thins around the bladder wall)

- Subcostal: this incision starts inferior to the xiphoid process, and extends inferior parallel to the costal margin. It is mainly used on the right side to operate on the gall bladder and on the left to operate on the spleen.

Describe the incision used in an Appendicectomy

Appendicectomy:

Incision at McBurney’s point

- 2/32 of the distance between the umbilicus and ASIS

- Through a ‘gridiron’ muscle-splitting incision

Gridiron Incision: put scissors in and open and close them to separate out the muscle fibres, followed by the next two layers. You have to separate out thee fibres of the external and internal oblique’s and the transversalis.

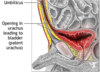

Explain about Patent Urachus and Vitelline Duct (developmental abnormalities)

- Patent Urachus: can present at birth or in later life in men when they develop bladder outflow obstruction due to benign prostatic hypertrophy – present clinically with urine coming out of the umbilicus

- Vitelline Duct (joins the yolk sac to the midgut) – can persist creating a number of different abnormalities such as Meckel’s Diverticulum

Explain about Meckel’s Diverticulum

Meckel’s Diverticulum: also known as Ilieal Diverticulum and is the most common GI abnormality. It is a ‘cul-de-ac’ in the ileum. Meckel’s Diverticulum follows a Rule of 2s:

- 2% of the population affected

- 2 feet from the ileocecal valve

- 2 inches long

- Usually detected in under 2’s, can be asymptomatic

- 2:1 Male:Female

The diverticulum can contain ectopic gastric or pancreatic tissue. The ectopic tissue will secrete enzymes and acids into tissue not protected from them, causing ulceration. The reason for this is not clear.

Explain about Vitelline Cyst and Vitelline Fistula

- VItelline Cyst: the vitelline duct forms fibrous strands at either end.

- Vitelline Fistula; there is direct communication between the umbilicus and the intestinal tract. This results in faecal matter coming out of the umbilicus.

What is Somatic Referred pain?

pain caused by a noxious stimulus to the proximal part of a somatic nerve that is perceived in the distal dermatome of the nerve. E.g. shingles affects nerves; pain is felt distally along the nerves from the problem

What is Visceral referred pain?

- in the thorax and abdomen, visceral afferent pain fibres follow sympathetic fibres back to the same spinal cord segments that gave rise to the preganglionic sympathetic fibres. The CNS perceives visceral pain as coming from the somatic portion of the body supplied by the relevant spinal cord segments.

- Visceral pain is caused by ischaemia, abnormally strong muscle contraction, inflammation and stretch

- Touch, burning, cutting and crushing does not cause visceral pain.

Where would you feel hepatic pain?

Where would you feel gastric and duodenal pain?

Where would you feel oesophageal pain?

Where would you feel pancreatic and abdominal aorta pain?

Retroperitoneal structures can cause central back pain e.g. pancreas and abdominal aorta

Where would you feel splenic pain?

Where would you feel gall bladder pain?