Reasoning and decision-making Flashcards

(30 cards)

Heuristics and biases (state)

- Availability

- how easy it is to bring instance to mind

- Representativeness

- based on similarity

- Anchoring

- assimilation of numeric estimate towards another value

Availability (heuristic)

Can be biased if experience doesn’t = true frequencies OR if ease to recall based on something other than frequency

Lichtenstein et al (1978) - estimate frequencies of causes of death

- overestimating low frequency events, underestimate high frequency events (e.g. heart disease)

- rare events receive disproportionate attention –> greater availability

Tversky & Kahneman (1973) –> recalled more famous names (more available)

- 12.3 famous recall vs 8.4 not famous /20

- conjunction fallacy: ease of recall bias: belief that conjunction of 2 events can have higher probability than either event individually

Tversky & Kahneman (1983) –> 4 page novel - number of -ing words vs number of -n- words

- 13.4 for -ing

- 4.7 for -n-

- even though -ing is a subset of -n-

Representativeness (heuristic)

Base rate neglect = similarity-based judgements are insensitive to prior probabilities

Kahneman & Tversky (1973)

- told profile pulled out of 70% engineer pool OR 70% lawyer pool

- probability of people saying he’s an engineer doesn’t change relative to pool

- based on prototype (similarity) instead

- given profile, list of 9 academic subjects

- told to judge:

- rank subjects by likelihood they specialise in it

- rank how typical they are of each group

- estimate proportion of all people that study it

- negative correlation for base rate estimation

- % of all people AND likelihood they specialise

- positive correlation for representativeness

- how typical + how likely

Anchoring (heuristic)

DEMONSTRATING

- Tversky & Kahneman (1974) –> wheel of fortune (10 vs 65)

- Chapman & Johnson (1999) - last 2 digits of SSN = anchor %

EXPLAINING

- Anchor + adjust –> start estimation from anchor + adjust (effortful cognitive work)

- BUT: you’d expect incentives would help people do better –> not the case

- Epley & Gilovich (2005)

- BUT: you’d expect incentives would help people do better –> not the case

- Anchor value changes our perception of magnitude of other candidate values

- Frederick & Mochon (2011)

- Externally presented anchors seen as a hint/suggestion even if uninformative

- participation bias?

Ecological rationality (state)

- mistakes made

Evolved or based on experience interacting with world

- Natural frequency formats = better

- Gambler’s fallacy

- Hot hand fallacy

- Representativeness

- Memory constraints

National frequency formats (ecological rationality)

Eddy (1982)

- medical professionals given probabilities of breast cancer given mammograms with FB rates

- 95/100 gave the wrong answer

- inverse fallacy: probability of cancer given a positive test = the probability of a positive test given cancer

- only 8% got it right

- people evolved to register counts not abstract percentages

- NB: bayes theorem would get right answer

- alter estimates based on new evidence + background information

- 95/100 gave the wrong answer

- Hoffrage & Gigerenzer (1998): eg above in natural frequency formats

- out of Z number of people, X have it and Y don’t

- 46% get it right

- we are better at understanding natural frequencies - makes more sense to us

- evolved to keep track of event frequencies by natural sampling (in this case, no need to take into account base-rate information)

Fallacies:

- gambler’s fallacy

- hot-hand fallacy

- memory constraints

Gambler’s fallacy = when random process throws up a streak of the same outcome, there will be a correction for it

- Croson & Sundali (2005) - witnessed in Nevada casino when streak of 4+ the same, people likely to bet against it

- Tversky & Kahneman (1971) - people expect local sequences to have properties of large sequences:

- in which case HTHTHT would be more likely than HHHHTTTT

Hot hand fallacy = infer streak is not representative of randomness - so streak will continue

- Gilovich et al (1985) - number of baskets scored in a row - believe if on a streak, they’ll make the next one

- because streak is not representative of randomness, they think it is not random + that it will continue

Ayton & Fischer (2004) - roulette style game:

- probability of predicting same as last time decreases as streak increases (Gambler’s)

- confidence in predicting skill increases as streak of successful predictions increases (Hot hand)

- SO: people take into account previous experience, intentional human performance + positive recency

- people view random mechanical outcomes as sampling without replacement (where odds DO decrease - for Gambler’s)

A&F (2004) –> 2 possible outcomes with different alteration rates

- if low AR - more likely to say it was basketball shots

- if high AR - more likely to say it was coin toss

- consistent with sampling without replacement + skill improvement

BUT: memory constraints

- Hahn + Warren (2009) - looked at mathematical properties of fair coin under realistic conditions

- there is a higher likelihood of high AR sequence for short/finite sequences

- these are the ones people see + remember

- so it is rational for people to expect T after long streak of H

- there is a higher likelihood of high AR sequence for short/finite sequences

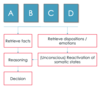

Why do people make mistakes on reasoning (about syllogisms OR propositional reasoning)

- Heuristics

- Comprehension

- Mental models

- Framing and experience

Syllogistic + propositional resoning

- what are they

- common mistakes

syllogisms + propositional reasoning –> 2 kinds of deductive reasoning

Syllogism = 2 premises then conclusion involving quantifiers: all, no, some, some…not

- All A are B, All B are C –> so All A are C

- 88% correct (Robert & Sykes, 2005)

- All B are A, all B are C –> so some A are C

- 8% correct (Robert & Sykes, 2005)

Propositional reasoning: about propositions containing conditionals (if, and, not, or):

- Schroyens et al (2001): ‘if A then B’ rule

- modus ponens (97% correct) = it’s A..so it’s B

- modus tollens (74%) = it’s not B..so not A

- affirmation of the consequent (64% commit it) = if B then A

- denial of the antecedent (56% commit it) = if not A then not B

Wason (1968) - 4 card selection task (D, K, 3, 7) –> rule = if D then 3 on other side

- only 1/34 turned over right cards to test rule (D+7)

Oaksford & Chater (1994) - rule = if p then q

- p=89%; not-p=62%; q=62%; not-q=25%

initial theory = confirmation bias - to show rule is true

Heuristics

- syllogisms

- propositional reasoning

SYLLOGISMS

- Atmosphere theory = people match ‘mood’ of premises to nood of conclusion

- quantity - can be universal (all/no) or particular (some, some not)

- quality - can be affirmative (all,some) or negative (no, some…not)

- Begg + Denny (1969) - 64 syllogisms, 4 possible conclusions (45/65 have no valid conclusion - how did people respond to them)

- when both premises were positive - 79% conclusions endorsed were positive

- when at least one premise was negative - 73% chosen conclusions were negative

- when both premises universal - 77% conclusions chosen were universal

- when at least one premise was particular - 90% chosen conclusions were particular

- BUT: doesn’t explain why sometimes people correctly endorse that there is no valid conclusion

PROPOSITIONAL REASONING

- Evans & Lynch (1973) 4 card task –> S, 9, G, 4: ‘if S then not-9’

- if confirmation bias - turn s and 4

- people turn S and 9

- Matching heuristic - turn cards mensioned in rule

Comprehension:

- syllogisms

- propositional reasoning

SYLLOGISMS:

- errors in syllogistic reasoning partly reflect use of language in formal logic vs every day use

- all A are B –> A=B

- some –> not all (but in logic can be all too)

- Ceraso & Provitera (1971) –> giving explanations/clarifying premises reduces error rates

- 58% with traditional format

- 94% correct with modified version

PROPOSITIONAL:

- Wagner-Egger (2007): bidirectional interpretation of ‘if’ (if A then B = if B then A) - common pattern of misunderstanding

- not an error or bias in selection task - just don’t understand rules

- Gebauer & Laming (1997) - the illogicality is only apparent, if people understand it they do fine

- BUT: doesn’t explain why people do worse on modus tollens than modus ponens

Mental models

- syllogisms

- propositional reasoning

SYLLOGISMS:

- Laird (2005):

- construct mental model of world implied by premises (comprehension)

- make a composite model + draw conclusion (description)

- validate by searching for alternative models and checking they don’t contradict conclusion (validation)

- more models = more likely conclusion right

- Copeland & Radvansky (2004):

- more possible models = less accurate + slower

- better working memory = more accurate + faster

- Newstead et al (1999) - no correlation between no. of models considered + accuracy

- people usually just construct 1 - multiple models are harder

PROPOSITIONAL

- initial model created relates to items mentioned in the rule

- explains why modus ponena easier than modus tollens

- can avoid affirmation of the consequent + denial of the antecedent if put in cognitive effort to flesh out models

Framing and experience

- syllogisms

- propositional reasoning

SYLLOGISMS:

- Evans et al (1983) –> if valid more likely to endorse it; if believable more likely to accept it

- belief bias = people don’t reason independently of experience or framing of problem

- Klaver et al (2000) –> base rates kick in when uncertain of conclusion - pushes reasoning after

- dual process framework

- if conclusion believable = only construct 1 model (consistent - verification

- if conclusion unbelievable = look for inconsistent models (tto falsify)

PROPOSITIONAL

- Giggs & Cox (1982) - beer, coke, 16, 25

- ‘if beer then over 19’

- if abstract - 0% correct

- if in context - 73% correct

- due to prior experience with rule

- BUT: Cosmides (1989) - even if no experience, context helps (due to social contract violation sensitivity)

- “If a man eats cassava root, then he must have a tattoo on his face” – still chance

- If give extra information – that cassava root eating is privilege of married men (married men have the tattoo) then performance increases to 75%

- BUT: Manktelow & Over (1990)

- “If you clear up spilt blood, then you must wear rubber gloves” (75% correct)

- but this is not a cost-benefit situation or social contract

- due to relevance/expected utility

- Girotto et al (2001) –> if going to X, must be vaccinated

- 62% correct –> going to X, not immunised (rule-violation sensitivity)

- if boss worried they made a mistake - don’t actually need it

- 71% check going to X and immunised

- information relevant to problem

Kinds of decision making

- Riskless multi-attribute choice

- 2+ options differing on 2+ attributes, no probability

- Intertemporal choice

- choosing between options available at different points in time

- Decisions under uncertainty

- don’t know in advance what the outcomes are (don’t know the probabilities)

- Decisions under risk

- 1+ of the possible outcomes are probabilistic (know the probability)

- THESE ARE THE ONES WE LOOK AT

Rational choice theory:

- expected value

- BUT issues

- expected utility theory

- BUT issues

EXPECTED VALUE

The EV of an option = sum of each possible outcome weighted by its probability

BUT: K+T (1979) - people risk averse for gains

- £3000 for sure over 80% chance of £4000

EXPECTED UTILITY

Transform actual value to subjective value

- explains risk aversion –> decreasing utility for higher rewards, less sensitive to increasingly large gains

BUT:

- people make decisions with respect to a starting point

- preference reversal –> risky when losses not gains –> EU only looks at end states (K+T, 1979)

- people weigh losses + gains differnetly - framing of the question alters choice (T+K, 1981)

Prospect theory

- explaining actual (seemingly irrational) behaviour of people

- the value function

- the decision weights function

K+T (1979):

- reference-dependence –> outcomes considered as gains/losses with respect to reference point

- risk attitudes –> risk averse for gains (decreasing sensitivity - concave); risk-seeking for losses (decreasing sensitivity - convex)

- Loss aversion - loss curve steeper than gain curve

- ‘losses loom larger than gains’

- EVIDENCE:

- Endowment effect (Knetsch, 1989): give mug or hot chocolate (reference point) - keep or swap

- loss feels worse than gains even if equally desirable at the start

- Endowment effect (Knetsch, 1989): give mug or hot chocolate (reference point) - keep or swap

- Decision weights function –> maps objective probabilities onto decision weights (W x V)

- small probabilities are overweightted

- large probabilities are underweighted

- steeper around 0+1 (near certainty) - more significant –> certainty effect

- Editing - when considering options, people round small amounts + combine probabilities with the same outcomes

Probability

- when people don’t act rationally

- against expected utility theory

Allais’ paradox (K+T, 1979)

- people treat 0%–> 1% chance differently from 66%–>67%

- starting point makes a difference –> violates rationality + EU

Certainty effect (K+T, 1981)

- change in probability has a greater effect if going from point of certainty than midrange

- making one option certain distorts probability judgement

Non-linear probabilities (Gonzalez & Wu, 1999)

- 5–>10% more significant than 30–>35%

- 65–>70% less significant than 90–>95%

- probabilities treated differently even if just near certainty

Problems with prospect theory

Limited scope

- valuation vs choice (Lichtenstein & Slovic, 1971) - p-bet (high prob.), $-bet (high value)

- 93% of people who chose the p-bet sell $-bet for a higher amound (want p but $ more valuable)

- only 17% showed reversal in other direction

Attraction effect (asymmetrical dominance

- Ariely (2009) - online ($59.99), online + print ($125), print ($125)

- 84% chose O+P

- if P removed, 68% chose O

- violates core assuption of rational choice theory –> independence from irrelevant alternatives

- Wedell (1991) - preference reversal if decoy more similar - attracted to option that dominates decoy

Empirical problem –> differing probabilities change risk-taking behaviour

- Weber & Chapman (2005) - high probability - people risk averse, low probability - different vanishes - more risky

- prospect theory would expect same difference (between % choosing low/high stakes) no matter the probability

Purely descriptive –> lacks mechanism to explain how people arrive at decision

- POSSIBLE RESPONSE: decision by sampling

Decision by sampling (mechanism of prospect theory)

Stewart et al (2006)

- when people given a value/probability, they turn it into subjective value by comparing it to other values available in memory

- cognitive mechanism of decision making

- Looked at bank credits –> put small amounts in more frequently (easy to map objective –> subjective value based on freq. of encounter)

- Looked at bank debits –> spend small amounts more frequently (spending small amounts = more frequent than saving small amounts)

- put numerical value to everyday english phrases used for probabilities - what people thought they were objectively

- overweighting of small probabilities

- underweighting of large probabilitites

- steep around 1 + ) –> same as decision weight function

Basic emotions

- what are they?

- views

- yes/no?

Universal emotions - culturally-ubiquitous

- Darwin (1872) - categorical idea:

- anger/fear/sadness/disgust/enjoyment (across species)

- Ekman (1992) –> basic emotions have rapid onset, brief duration, unbidden occurrence, distinctive signs, physiological correlates

Dimensional view:

- Russel & Barrett (1998) : core affect –> arousal + valence (pleasant/unpleasant) dimensions (high to low)

NOT universal (Gendron et al., 2018)

- depends on culture + definition of emotion

- 1975-2008 –> moderate-strong evidence for universal expression of emotions

- 2008-2018 –> no strong, 2 moderate, 9 weak evidence

Physiology of emotions

- for and against specific physiology

James-Lange view (James 1884; Lange 1885):

- stimulus –> percept –> physiology –> emotion

- emotion = product of somatic/physiological change

NO:

- Cannon (1927) - people without peripheral inputs still experience emotion

- peripheral arousal doesn’t create emotion

- peripheral states no sufficiently differentiated per emotion

- Siegel et al (2018) –> metaanalysis - prediction of emotion from physiology = 31-32% correct

- almost the same as if angry were guessed for all

Role of cognition in emotion

Schachter (1964) the effect of somatic arousal depends on its attribution - how it’s interpreted given the social context

Schachter & Singer (1962) –> physiological arousal provides raw ingredients, cognition defines the emotion

- given ‘suproxin’ (adrenaline) + told side effects –> attribute arousal to the pill

- stooge not that effective (euphoric or angry)

- given suproxin + not told side effects –> attribute arousal to mood as result of stooge (euphoric –> positive mood; angry –> negative mood)

Zajonc et al (1980): rejects role of congition in emotion

- previously-encountered stimuli elicit more positive affect than novel do, even if no conscious awareness of having seen it

Scherer (1984) –> appraisal theorist –> cognitive appraisals underlying emotion need not be conscious

- various appraisal dimension shape emotion: certainty, control, responsibility of others, attention

Common ground of contemporary views of emotion

Scherer & Moors (2019) - review:

- multi-level appraisals –> cognitive components - evaluation of memories/event/stimuli

- physiology - physical responses in body

- action tendencies - propensity to behave in certain ways

- motor expression - facial expression, voice tone, body language, gestures

- component integration-experienced feeling –> subjectively what it’s like to feel an emotion

- no one-to-one mapping - all integrated

Amygdala lesions and emotion

- Blanchard & Blanchard (1972)

- reduced fear conditioning - decreased capacity to learn to be afraid of something

- Calder et al (1996)

- failure to recognise fear from face photos (mean = 4/10 vs control = 8.6/10)

- Adolphs et al (1997)

- decreased memory of emotional components of narrative (usually strongest)

- Hamann et al (1999)

- better encoding of emotional info = more excitation in amygdala