Session 6 Flashcards

(42 cards)

Describe and state the normal range of plasma pH

[*] Normal cellular function depends critically on ECF pH which must be maintained within very narrow limits.

[*] This is achieved by an interaction between the respiratory and renal systems controlling different components of the buffer system that stabilise ECF pH.

[*] The normal range of plasma pH is 7.38-7.45, which is a concentration of between 37-43 nmol/L of H+

[*] If the pH is below this range, the condition is known as acidaemia.

[*] If the pH is above this range, the condition is alkalaemia and alkalaemia is more dangerous than acidaemia.

[*] The kidneys control plasma pH by filtering and variably recovering hydrogen carbonate and active secretion of hydrogen ions

Describe the clinical effects of acidaemia

[*] Acidaemia affects enzyme function in many tissues and leads to potassium movement out of cells => hyperkalaemia which can be fatal.

Affects many enzymes:

- Alters excitable tissues such as cardiac muscle – reduced cardiac and skeletal muscle contractility

- Reduced glycolysis in many tissues

- Reduced hepatic function

- Increased plasma potassium

The effects can be severe at pH’s below 7.1 and life threatening below 7.0

Describe the clinical effects of alkalaemia

[*] Alkalaemia reduces the solubility of calcium salts, which means that free Ca2+ leaves the ECF, binding to bones and proteins.

- The resulting hypocalcaemia makes nerves much more excitable, producing paraesthesia (abnormal sensations) and eventually uncontrolled muscle contractions – tetany.

- If the pH rises above 7.55, 45% of patients die.

- Above 7.65, the mortality is 80%

Describe the carbon dioxide/hydrogen carbonate buffer system

[*] As the H+ ion concentration in ECF is so low, the addition of very small amounts of acid would change the concentration and therefore pH dramatically. This does not happen because H+ ions are buffered by binding to various sites.

[*] The most important ECF buffer is the carbon dioxide / hydrogen carbonate system:

CO2 + H20 < = > H+ + HCO3-

[*] The extent to which the reversible reaction proceeds is determined by the ratio of [HCO3-] to [Dissolved CO2]. Ideally the ratio should be 20:1

- Dissolved CO2 is determined by the pCO2 of plasma, which is controlled by the lungs.

- HCO3- is largely created by reactions in the red blood cells, but concentration of HCO3- is controlled by the kidney

- Disturbed by metabolic and renal diseases

[*] The Hendelson-Hasselbalch equation describes this relationship: pH = 6.1 + log [(HCO3-) / (0.23 x pCO2)]. pCO2 is expressed in kPA and and [HCO3-] in mmol/L

[*] Normal pCO2 is between 4.2 and 6.0 kPa (maintained by breathing)

- Controlled by chemoreceptors

- Disturbed by respiratory diseases

[*] Normal [HCO3-] in plasma is 22-29 mmol/L (~25mmol/L)

[*] At the mid-range of pCO2 of 5.4kPA and HCO3- of 24 mmol/L, the pH will be 7.3

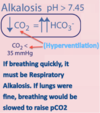

Describe respiratory alkalaemia

[*] Falls in pCO2 produce respiratory alkalaemia (respiratory alkalosis is technically incorrect) – pH>7.45

- Hyperventilation leads to hypocapnia

- Falls in pCO2 causes pH to rise (ratio gets bigger as there is more than 20x the amount of HCO3- than CO2, so relatively more H+ ions are buffered, causing the pH increase)

Describe respiratory acidaemia

[*] Rises in pCO2 produce respiratory acidaemia (respiratory acidosis is technically incorrect) – pH < 7.35

- Hypoventilation leads to hypercapnia

- Hypercapnia causes plasma pH to fall (there is less than 20x the amount of HCO3- than CO2 so relatively less H+ ions are buffered, causing the pH to decrease).

How may respiratory alkalosis and acidaemia be compensated?

[*] Central chemoreceptors normally control pCO2 within tight limits.

- Respiratory changes CORRECT respiratory disturbances of pH

- Peripheral chemoreceptors enable changes in respiration driven by changes in plasma pH

[*] As the pH depends on the ratio of [HCO3-] and pCO2, not absolute values, respiratory acidaemia or alkalaemia can be COMPENSATED for by changes in [HCO3-] produced by the kidney.

[*] If the pCO2 rises, a proportionate rise in [HCO3-] will restore pH. If the pCO2 falls, a proportionate fall in [HCO3-] will restore pH (by restoring the ratio) These compensatory changes are produced by variable renal excretion or production of HCO3-. The original problem still occurs.

- Respiratory acidaemia (acidosis) is compensated by the kidneys increasing [HCO3-]

- Respiratory alkalaemia (alkalosis) is compensated by the kidneys decreasing [HCO3-]

Describe metabolic acidosis

[*] If H+ ions are produced metabolically in the tissues (e.g. from metabolism of amino acids or production of ketones), they react with HCO3- to produce CO2 in venous blood, which is then breathed out through the lungs, leaving a directly proportional deficit of [HCO3-] in arterial blood (one mmol acid added to blood will remove one mmol HCO3-). This alters the [HCo3-]: pCO2 ratio meaning that there is less than 20x the amount of HCO3- than CO2. Relatively less H+ ions are buffered, causing a pH decrease.

Reductions in [HCO3-] are known as metabolic acidosis (pH <7.35)

Describe metabolic alkalosis

[*] Increases in [HCO3-] are known as metabolic alkalosis (pH > 7.45) e.g. after persistent vomiting

There is more than 20x the amount of HCO3- than CO2 will be present so relatively more H+ ions are buffered, causing a pH increase.

How can metabolic acidosis and metabolic alkalosis be compensated?

- These changes may be compensated by altering pCO2 by changing ventilating

- pCO2 is normally kept within tight limits by the Central Chemoreceptors

- Changes in plasma pH drive chains in pCO2 via the Peripheral Chemoreceptors

- In metabolic acidosis, pCO2 is lowered proportionately by increasing ventilation.

- In alkalosis, pCO2 can be slightly raised by decreasing ventilation but compensation is limited (partial compensation) by hypoxia resulting from hypoventilation

- Correction depends upon the kidney variably excreting or creating HCO3-. The handling of hydrogen carbonate by the kidney is therefore critical for maintaining acid base balance.

Describe and be able to identify from values, respiratory acidaemia (acidosis) and alkalaemia (alkalosis) and metabolic acidosis and alkalosis

[*] Respiratory Acidaemia (acidosis): hypoventilation has raised pCO2. Hypercapnia leads to low pH. [HCO3-] is unchanged.

[*] Compensated (partially or fully) Respiratory Acidaemia: Kidneys have increased [HCO3-]. This increases the buffering of H+ ions caused by increased pCO2.

[*] Respiratory alkalaemia (alkalosis): Hyperventilation has lowed pCO2. Hypocapnia leads to high pH. [HCO3-] unchanged.

[*] Compensated (partially or fully) Respiratory Alkalaemia: kidneys have decreased [HCo3-]. Decreased buffering of H+ ions.

[*] Metabolic Acidosis: Decreased [HCO3-] leads to less buffering of H+ ions. Increase in unmeasured anions (anion associated with the increase in H+ has taken [HCO3]’s place.

[*] Compensated (partially or fully) Metabolic Acidosis: increased respiratory rate => hypocapnia => raised pH. Anion gap still increased.

[*] Metabolic Alkalosis: increased [HCO3-] leads to buffering of H+

[*] Compensated (partially or fully) Metabolic Alkalosis: decreased respiratory rate => hypercapnia => decreased pH. Can only partially compensate

See Groupwork and actual notes + lusuma notes

Describe the renal control of HCO3-

[*] Hydrogen carbonate is filtered in considerable quantities at the glomerulus – at 180mmol/hour or 4500mmol/day.

[*] This needs to be recovered to maintain acid base status unless the patient is alkalotic.

[*] If the acid is produced metabolically, recovery of all filtered [HCO3-] will be insufficient to restore plasma [HCO3-] so HCO3- will have to be created within the kidney

[*] This will create H+ ions which are then excreted directly or indirectly into the urine, and to avoid a damaging urinary acidity, it must be buffered by either other filtered substances or buffers created by the kidney.

- Metabolic activity of kidney produces large quantities of CO2 which can react with water to produce:

- HCO3- to enter plasma

- H+ to enter urine (but if urine becomes too acidic, this could damagae urinary tract)

[*] Can also make hCO3- from amino acids, producing NH4- to enter urine

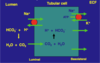

Describe cellular mechanisms of reabsorption of HCO3- in the proximal tubule

[*] A large fraction of HCO3- is reabsorbed in the proximal tubule. H+ ions are pumped out of the apical membrane of the proximal tubule cells in exchange for the inward movement of Na+ ions down its concentration gradient.

- H+ exported from cell into lumen (up concentration gradient)

- Up concentration gradient

- Energy from movement of Na+ down concentration gradient (produced by sodium pumps on basolateral membrane)

- H+ reacts with HCO3- - making CO2 which enters cells

- To react with H20 and recreate H+ which is exported again

- Leaving HCo3- to leave by basolateral membrane to ECF.

[*] 80-90% of the filtered HCO3- is reabsorbed in the proximal tubule.

[*] Up to 15% of HCO3- is also absorbed in the thick ascending limb of the loop of Henle by a similar mechanism. (Remember ascending limb is known as the diluting segment – of urine – as it is impermeable to water)

Describe creation of HCO3- inside the proximal tubule

Glutamine is broken down to produce

- Alpha-ketoglutarate which makes HCO3- and ammonium (NH4+)

- HCO3- into ECF

- NH4+ into lumen => urine

Describe cellular mechanisms of H+ absorption andexcretion in the distal tubule

[*] HCO3- absorption and H+ excretion occur through intercalated cells in the distal nephron.

[*] H+ is pumped across the apical membrane by a H+-ATP’ase pump as the Na+ ion gradient is insufficient to drive H+ out of the cell. These proton pumps are similar to those found in the stomach.

[*] By this stage there is very little HCO3- remaining, so little CO2 enters the cell to react with water and create H+ for excretion. This is produced from CO2 produced by the cells’ own metabolism, so generating new HCO3- to enter the plasma.

[*] When the cells export H+, K+ is absorbed into the blood. So if you export a lot of H+, you will also absorb a lot (perhaps too much) K+. This relationship means that blood pH is linked to [K+].

Describe the creation of HCO3- inside the distal tubule

- By the distal tubule, all filtered HCO3- is normally recovered.

- Na gradient is insufficient to drive H+ secretion

- So active secretion of H+ into lumen is needed.

- In the lumen H+ is buffered by filtered phosphate and excreted ammonia

- H+ is generated is from metabolic CO2 which also produces HCO3- which enters ECF

Describe the mechanism of buffering of H+ in urine and explain the concept of titratable acid, and the role of NH4+

[*] Minimum urine pH is 4.5 ([H+] of 0.04mmol/L)

[*] Some H+ is buffered by phosphate. Phosphate is a titratable acid, meaning that it can freely gain H+ ions in an acid/base reaction.

[*] Total acid excretion 50-100 mmol H+ per day – keeps plasma [HCO3-] normal

[*] Most of the excreted H+ reacts with buffers and remains in the urine.

[*] One such buffer – monobasic phosphate (HPO2^-4) becomes more effective as the pH of urine falls.

[*] The total buffering capacity of phosphate and the other weak acids is however limited by the amount filtered and the replacement of any further HCO3- needs to take place by a mechanism within the kidney: the excretion of ammonium ions.

[*] Ammonium ions are produced from the amino acid glutamine (Glut)

[*] Each alpha-ketoglutorate yields two HCO3- which enters the blood stream (in effect, this is indirect excretion of H+ attached to ammonia). This process takes place largely in the proximal tubule, but is supplemented distally.

[*] Glut => NH4+ + glutamate => NH4+ + alpha-ketoglutorate

[*] Overall, the kidney is able to both recover the filtered HCO3- and replace any, which has been removed from the blood by the buffering of metabolic acid.

Describe control of H+ excretion and cellular responses to acidosis

[*] Control of H+ excretion:

- Stimulus to changes in acid secretion probably changes in intracellular pH of tubular cells

- Due to changes in rate of HCO3- export to ECF produced by changes in ECF [HCO3-]

[*] Cellular responses to acidosis:

- Enhanced H+/Na+ exchange – full recovery of all filtered HCO3-

- Enhanced ammonium production in proximal tubule

- Increased activity of H+ ATP-ase in distal tubule (expel more H+ ions)

- Increased capacity to export HCO3- from tubular cells to ECF

Describe the interactions between acid base status and plasma [K+]

[*] Acid secretion increases as ECF pH falls, probably due largely to changes in renal tubular pH consequent upon changes in the rate of export of HCO3- to plasma, indicating that in reality it is [HCO3-] which is sensed and controlled rather more than pH per se.

[*] In respiratory acidaemia or alkalaemia, renal tubular pH is probably affected directly by changes in the rate of diffusion of CO2 into the cells as pCO2 alter.

[*] Plasma potassium concentration also influences HCO3- reabsorption and ammonium excretion, so that as [K+] rises, the capacity of the kidney to reabsorb and create HCO3- is reduced.

[*] Metabolic alkalosis is associated with hypokalaemia – K+ moves into cells and there is less K+ reabsorption (more K+ excretion occurs as more HCO3- is reabsorbed) so extracellular fluid [K+] is low.

[*] Hypokalaemia makes intracellular pH of tubule cells acidic – favours H+ excretion and HCO3- recovery and therefore metabolic alkalosis

[*] Metabolic acidosis is associated with hyperkalaemia – K+ moves out of cells into plasma and more K+ reabsorption in distal nephron (as more HCO3- is excreted)

[*] Hyperkalaemia makes intracellular pH alkaline – favours HCO3- excretion and therefore metabolic acidosis.

Describe the interaction between renal control of acid base balance and control of plasma volume

[*] HCO3- increases after persistent vomiting (loss of acid, volume and electrolytes)

[*] HCO3- infusions are excreted extremely rapidly (no loss in volume) as the rise in intra-cellular pH reduces H+ excretion and HCO3- recovery. So the body corrects this very easily

[*] But in vomiting, especially vomiting associated with diarrhoea, there is also volume depletion. The capacity to lose HCO3- is less because of high rates of recovery of Na+ is prioritised HCO3- recovery and H+ secretion as well. The kidneys will sort out dehydration before alkalosis – Na+ recovery increases the osmolarity of the plasma and causes the osmotic movement of water

[*] In this case you cannot rely on the kidneys to correct the [HCO3-], however if you correct the dehydration by giving fluids, hCO3- will be excreted very rapidly.

Describe the common causes of metabolic alkalosis, in particular the effects of persistent vomiting

[*] [HCO3-] increases after persistent vomiting (metabolic alkalosis), so the body stops actively secreting H+, as it would make metabolic alkalosis worse.

[*] As H+ secretion has stopped, so has K+ reabsorption (antiporter in intercalated cells). This means that a dangerous side effect of persistent vomiting is hypokalaemia, which causes paresthesia, tetany and CVS problems

Describe the main classes of metabolic acidosis, and the role of anion-gap measurements in distinguishing between them.

[*] Metabolic acidosis will occur if there is excess metabolic production of acids (lactic acidosis, ketoacidosis), excess acids are ingested, HCO3- is lost or there is a problem with the renal excretion of acid.

[*] H+ reacts with HCO3- , producing CO2 which is breathed out. If excess acid is produced, the associated anion (e.g. lactate, ketone) will replace HCO3- in plasma, which will influence the anion-gap.

[*] The anion-gap is the difference between the sum of the measured concentrations sodium and potassium ions, and the sum of the measured concentrations of the chloride ions and hydrogen carbonate.

[*] The anion gap indicates whether any HCO3- has been replaced with something other than Cl- (measurement made in order to found out why someone has metabolic acidosis)

[*] If hydrogen carbonate is replaced by another anion which is not included in the calculation, the gap will increase.

[*] If the problem lies with the renal excretion of H+ ions this will change the [HCO3-] directly without replacement by an unmeasured ion, so the anion-gap is less likely to change. (HCO3- is replaced with Cl-)

[*] Normally 10-15 mmol/L

[*] Fall in tubular cell intracellular pH stimulates acid secretion and HCO3- recovery so raising plasma [HCO3-]

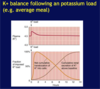

Describe why the internal balance of potassium is so important

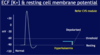

[*] Potassium ions are the most abundant intracellular cation. Some 98% of the total body potassium content (150-160 mmol/L is intraceullar or ~50mmol/kg body weight)

[*] The body tightly maintains the plasma [K+} to a range of 3.5-5.3 mmol/L

[*] The high [K+]i inside the cell and the low [K+]e outside creates a gradient for K+ to move out of the cell => creates resting membrane potential. The inside of the cell is negatively charged compared to the outside.

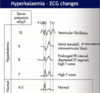

[*] The potentially life threatening disturbances of cardiac rhythmicity that result from a rise of plasma [K+] are particularly important (CVS unit)

[*] Extremely low ECF [K+] )chronic K+ ion depletion) leads to several metabolic disturbances which include: the inability of the kidney to form concentrated urine, a tendency to develop metabolic alkalosis, and an enhancement of renal ammonium excretion.

[*] 2 homeostatic mechanisms keep the ECF [K+] tightly controlled - external and internal balance.

- Small increases in the serum potassium concentration can be very quickly life threatening

- The kidneys cannot excrete potassium quickly enough to contain surges in oral potassium loads hence intracellular buffering plays an important role in potassium homeostates.

- As the kidneys excrete the excess and serum concentration falls, K+ is released again from the cells.

Describe the physiological roles of having a high intracellular [K+]

[*] High [K+] inside cells and inside mitochondria is essential for maintaining cell volume, for regulating pH and controlling cell-enzyme function, for DNA and protein synthesis and for cell growth. The physiological roles of intracellular potassium are:

- Cell volume maintenance: net loss of K+ => cell shrinkage and net gain of K+ => cell swelling

- Intracellular pH regulation: net loss of K+ => cell acidosis, net gain of K+ => cell alkalosis

- Cell enzyme functions: K+ dependence of enzymes e.g. some ATPases, succinic dehydrogenase

- DNA/Protein Synthesis, Growth: lack of K+ => reduction of protein synthesis, stunted growth