Cardiology 534/16 Flashcards

- Peripheral Arterial Disease - History

Classical symptoms of intermittent claudication

- pain is located in a lower limb muscle group, brought on by exercise and relieved by rest.

Classical symptoms of rest pain

- severe pain located in the foot, present for at least four weeks, worse on leg elevation (eg in bed) and relieved by lowering the foot to the ground.

Other history

- gangrene

- lower limb ulceration

- ischaemic heart disease or cerebrovascular disease; specifically about

–> symptoms related to those vascular beds (eg exertional chest pain/tightness, past focal neurological symptoms typical of transient ischemic attack or stroke

History of risk factors for atherosclerosis

- hypertension*

- diabetes*

- dyslipidaemia*

- smoking*

Current medications should be recorded, as should allergies and family history of cardiovascular disease.

The functional effect of the pain on Ken’s life should be estimated. For example, is it stopping him from enjoying a significant range of activities?

- Peripheral Arterial Disease- Examination

General examination cardiovascular system

- lower limbs should be examined, looking for evidence of poor perfusion, such as skin changes (reduced capillary refilling, cold periphery and pallor) and reduced or absent pulses.

- Ankle:brachial index (ABI) should also be measured

- Peripheral Arterial Disease- DDx

A differential diagnosis would be spinal claudication.

It is important to note that patients with PAD may present with atypical symptoms, or indeed no symptoms, as the exercise tolerability may be limited by other disease processes.

A significant number of patients with PAD also have abdominal aortic aneurysms (AAAs) so screening them for an AAA is suggested.

Pain location can vary with location of the disease, from the buttock to the foot.

[Claudication, from the Latin ‘to limp’- named after the Roman Emperor Claudius, who was said to have walked with a limp]

- Peripheral Arterial Disease- Dx

ABI (<0.9) is a reliable indicator of the PAD, providing the appropriate equipment is available.

ABI is usually measured with a hand-held Doppler and an appropriate blood pressure cuff, although there are more expensive devices available for this.

Arterial duplex ultrasonography (and computed tomography angiography) can identify sites of occlusion or stenosis but requires a highly experienced sonographer to provide reliable information.

ABI alone is adequate prior to referral to a specialist, who can decide whether further imaging is appropriate.

- Peripheral Arterial Disease- Mx

Medical management is the priority as PAD is a sign of generalised vascular disease.

- prescriptions for antihypertensive and cholesterol-lowering medication despite not crossing individual risk factor thresholds

–> An angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor (eg ramipril) or calcium channel blocker (eg amlodipine) and a statin (eg atorvastatin or rosuvastatin) are recommended.

–> Beta-blockers are best avoided unless required for cardioprotection.

–> The aim is to improve circulation and walking distance, but maximally tolerated medication is also required because of this high risk for cardiovascular events.

Antiplatelet medication is also indicated (eg aspirin 100 mg).

Supervised exercise programs are effective at improving symptoms but not currently funded by the healthcare system in Australia.

Smoking cessation

Revascularisation procedures are usually only considered if symptoms are severe or if tissue destruction is evident.

Referral to a vascular specialist is recommended for patients with lifestyle-limiting intermittent claudication, rest pain and gangrene.

Patients with rest pain, arterial ulcers or gangrene should be seen urgently.

Revascularisation is considered for lifestyle-limiting intermittent claudication, but has associated risks and is frequently not durable on its own.

This highlights the importance of lifestyle changes and medical management as first-line treatment.

- Familial Hypercholesterolaemia- History and Examination

A full medical history; particular attention to cardiovascular history is required.

- detailed family history of cardiovascular disease (CVD) and lipid disorder is also indicated.

A routine cardiovascular examination

+ specifically looking for peripheral signs of lipid disorders should be done

–>tendon xanthomata, fatty deposits in tendon sheaths and

–>premature arcus cornealis, the presence of a white ring of lipid deposit around the margin of the cornea in a patient under the age of 45 years.

–> Xanthelasma palpebrarum, flat, lipid-rich growths on the eyelids, are commonly associated with elevated cholesterol and increased risk of coronary heart disease (CHD), but are not particularly predictive of inherited hypercholesterolaemia.

- Familial Hypercholesterolaemia

While lifestyle factors, diet, exercise and metabolic disease are the most likely causes for cholesterol abnormalities in the general population, high (LDL-C) levels and family history can be strongly suggestive of an inherited cholesterol defect.

The most common of these is FH. It is estimated to occur with a frequency of at least 1 in 500 in the general population, and at higher levels in selected populations such as people from Mediterranean countries, Christian Lebanese, French Canadians and Afrikaner South Africans.

It is autosomally dominant, so that in a family with an index case of FH, the likelihood of other first-degree relatives having FH is 50%.

If both parents are carriers, the likelihood of FH increases to 75% with a 25% chance that an offspring will be homozygous for FH, a rare but much more severe form of the disease.

Critically, FH is underdiagnosed; only 10–15% of cases are formally identified.

GPs underestimate the prevalence of FH in their own practice population.

The risk of premature atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (CVD) is raised many times in patients with FH, in some by 25 times the population risk.

- Familial Hypercholesterolaemia Dx

Diagnosis can be made on

- clinical findings,

- history,

- examination and

- fasted, untreated LDL-C levels.

An LDL-C of >5 mmol/L raises the suspicion of FH.

The likelihood of FH can be quantified using a tool such as the DLCNS, a diagnostic algorithm that incorporates the patient’s cardiovascular history, family history, clinical findings, such as arcus cornealis and tendon xanthomata, and their LDL-C level to give a score and probability level of FH.

- Familial Hypercholesterolaemia- confounding factors

Important confounding factors that can contribute to hypercholesterolaemia, for which the patient must be screened before making the diagnosis of FH include

- nephrotic syndrome,

- diabetes,

- hypothyroid disease and

- corticosteroid use

- Familial Hyperchlolesterolaemia- management

FH can be subdivided into

Low- complexity cases can be managed in primary care by the patient’s general practitioner.

Intermediate complexity includes patients with CVD risk factors and/or minor issues around achieving ideal LDL-C levels and should involve shared care between the GP and an FH specialist centre.

High-complexity cases will involve patients with multiple cardiovascular risk factors and difficult-to-control LDL-C levels, and should be managed by an FH specialist centre.

- Familial Hypercholesterolaemia- management

Clinical priorities include three important dimensions

Treatment; inherited metabolic disorder of cholesterol, which has been present and active from birth high likelihood of vascular diseaseat diagnosis is very high and will increase the longer he is untreated. He should be screened for existing coronary artery disease.

Second, he may need specialist involvement and genetic testing. While management of low-complexity cases of FH is well within the scope of GPs, specialist involvement can assist with difficulties with treatment options, rare cases of homozygous FH, provision of genetic testing and cascade screening of affected families. Genetic testing can confirm the diagnosis and streamline further case discovery within families.

The third priority is discussion with Doug about cascade screening of his relatives. Cascade screening is the term used for screening family members of an index case of FH. It is the most cost-efficient way of finding new cases of FH. Cascade screening involves important discussions around disclosure of confidential health information and legal and ethical risks around discovering genetic disease in clinically unaffected family members.

Cascade screening services may be offered by some specialist clinics. Doug has a sibling and three children who are at risk of FH, and may be diagnosed and treated before significant atherosclerosis occurs. Screening of children remains controversial, but should definitely be considered in families affected by FH3, or with a strong family history of premature atherosclerotic CVD.

- Familial Hypercholesterolaemia- Inx

Further investigations include

- fasting glucose testing to screen for diabetes

- thyroid function tests for thyroid disease

- and proteinuria for renal disease, if not already done.

In addition, if starting a statin it is worth checking liver function enzymes in the first 4–12 months.

- Familial Hypercholeterolaemia- Rx

First-line management

- advice about lifestyle risks for CVD, including diet, exercise, smoking, and treatment with a cholesterol-lowering agent

–> a high-potency statin in most patients.

–> Other agents may be required if statins cannot be tolerated because of side effects, or if there is incomplete treatment of LDL-C levels include ezetimibe and bile acid sequestrants.

Target levels for treatment are an

- LDL-C <2.5 mmol/L with no CVD, and

- 1.8 mmol/L with evidence of CVD.

Referral to specialist lipid and/or cardiology services should be considered for several reasons

- current coronary artery status should be assessed. Computed tomography (CT) coronary angiography is a useful tool in excluding pre-existing atherosclerotic CVD in patients at low-to-intermediate risk. Under the current Medical Benefits Schedule (MBS), this is restricted to specialist or consultant physician referral.

Currently in Australia, use of CT coronary angiography in the asymptomatic patient remains controversial. If FH has been formally diagnosed there may be a stronger case to proceed.

- Genetic testing should be considered. Identification of the genetic mutation allows better prognostic evaluation of the dyslipidaemia. It may facilitate novel treatments in more complex cases of FH. It also enables the accurate identification of family members at risk.

- HTN - assessment

Establishing a diagnosis of hypertension

- 24hr ABPM or home BP measures

Determining the severity of hypertension

Ruling out secondary causes of hypertension, including

- screening for obstructive sleep apnoea (eg using the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index)

assessing contributing lifestyle and other modifiable risk factors for CVD

assessing for complications/target organ damage

assessing the absolute CVD risk.

Other preventive activities include:

comprehensive smoking assessment and smoking, nutrition, alcohol and physical (SNAP) risk factor assessment

history of screening activities – relevant ones including

- cervical cancer screening,

- breast cancer screening,

- colorectal cancer screening,

- osteoporosis screening (coupled with determination of menopause status).

- ? * Prostate cancer

- HTN- Examination

urinalysis (protein and blood in the urine may indicate end-organ renal disease)

listen for carotid artery bruits

examine the fundi for hypertensive changes

examine the peripheral vascular system for evidence of arterial disease

record an electrocardiogram (ECG) to look for left ventricular hypertrophy and ischaemic changes

examine the abdomen:

looking for evidence of arterial disease (eg abdominal aortic aneurysm and renal bruits that may indicate renal artery stenosis),

and ballot the kidneys for polycystic kidney disease.

- HTN - Inx

It is appropriate to check:

fasting cholesterol and lipids

blood glucose levels

electrolytes and renal function

urine examination, especially urinary albumin-to-creatinine ratio (UACR) to exclude end-organ damage from hypertension and exclude renal parenchymal disease that may contribute to high blood pressure.

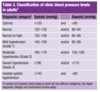

- HTN - Severity

- HTN- CVD risk assessment

It is recommended that the Australian absolute cardiovascular disease risk calculator (an initiative of the National Vascular Disease Prevention Alliance and endorsed by RACGP) be used to determine a patient’s CVD risk.

The Australian absolute cardiovascular disease risk chart and calculator are based on the results obtained from the Framingham heart study – a long-term cohort study of more than 5000 people living in the town of Framingham in Massachusetts, US. It is useful for estimating the cardiovascular risk but has several limitations.

- it does not take into account a person’s family history, ethnicity, body mass or waist circumference, or other associated conditions except for diabetes. The use of the chart in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander patients may result in underestimation of their risk, so it should be used carefully in this patient group. However, available evidence suggests that this approach will provide an estimate of minimum CVD risk.

It is recommended that absolute CVD risk assessment be performed regularly in all adults aged 45 and older (or 35 years and older for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples) without existing CVD or not already known to be at increased risk of CVD. The calculator should not be used in those that are already at increased (high) risk of cardiovascular disease. These patient groups include those with:

- diabetes and aged >60 years

- diabetes with microalbuminuria (>20 μg/min or UACR >2.5 mg/mmol for males and >3.5 mg/mmol for females)

- moderate or severe chronic kidney disease (persistent proteinuria or estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) <45 mL/min/1.73 m2)

- patients with familial hypercholesterolaemia

- systolic blood pressure ≥180 mmHg or diastolic blood pressure ≥110 mmHg

- serum total cholesterol >7.5 mmol/L.

- HTN - management

Advice on lifestyle changes is paramount in managing CVD risk and blood pressure.

This includes SNAP risk factors – smoking cessation, nutrition, alcohol and physical activity.

Dietary advice should include

- lowering salt intake,

- reducing saturated fat intake,

- avoiding eating liquorice, and

- increasing the intake of oily fish and dietary fibre.

Encouraged to be active – most guidelines recommend at least 30 minutes a day, five days a week of moderate intensity aerobic exercise.

Referral to a dietitian or exercise physiologist may be useful.

Motivational interviewing and the use of the 5As framework (www. racgp.org.au/your-practice/guidelines/smoking-cessation/the-5-as- structure-for-smoking-cessation), including pharmacotherapy could be used to help quit smoking.

Stress may also be contributing to her high blood pressure. Counselling, advice on relaxation and stress reduction techniques may prove to be helpful. Referral to a psychologist or counselling service may be required if not responding to interventions intiated by the general practitioner.

Initially, should be trialled on non-pharmacological management for a few weeks. Given she has intermediate CVD risk (10–15% over five years), if blood pressure remains above 140/90 mmHg despite lifestyle changes, then pharmacological treatment is indicated.

On the other hand, if CVD risk were <10% (ie low risk), then antihypertensive therapy would be recommended only for persistently high blood pressure ≥160/100.

Once a decision has been made to start antihypertensives, consideration should be given to starting a statin to further reduce her CVD risk. The benefits of statins in reducing CVD risk appears to go beyond what may be expected from the reduction in cholesterol levels. Because she has hypertension, if total cholesterol remains >5.5 mmol/L and HDL <0.9 mmol/L after six weeks of lifestyle changes, then patient would qualify for Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme (PBS) subsidy.

- HTN - Target levels

Until recently, it was recommended that patients should aim for a blood pressure target of 140/90 mmHg when titrating medications (higher in elderly or those with side effects).

However, the results of a large randomised controlled trial (the SPRINT study) showed that patients whose medications were titrated to a more intensive lower blood pressure target had significantly better outcomes compared with those with a higher target.

Therefore, the revised 2016 National Heart Foundation of Australia’s guidelines recommend that in selected high CVD-risk populations (ie in those with an estimated absolute CVD 10-year risk of at least 20% who were recruited into the SPRINT trial), a more intense treatment can be considered, aiming for a target of <120 mmHg systolic blood pressure to improve CVD outcomes (grade of recommendation = strong, level of evidence = II). This would be more important in those with end-organ damage or existing CVD, or those with significant risk factors. These patients will need to be monitored carefully for symptoms of postural hypotension and other adverse effects (eg hyperkalaemia in patients taking angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor or angiotension receptor antagonist).

- HTN - Additional agents

It is preferable to start on a second medication.

Maximising the dose of one medication may result in more side effects and may not result in satisfactory control of the blood pressure.

If taking an angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor, which is an appropriate first-line agent for hypertension. An angiotension receptor II antagonist is an acceptable alternative, but the two should not be prescribed together because of the risk of side effects (hyperkalaemia and increased risk of renal dysfunction).

The second agent could be a calcium channel antagonist.

Thiazide diuretics could also be considered.

Beta-blockers, while not contraindicated, are not recommended at this stage because of adverse effects profile, unless patient has pre-existing ischaemic heart disease.

- Congenital Heart Disease- History

Symptoms arising from congenital heart disease vary widely.

Infants may initially present with failing to thrive and a history of short, frequent feeds. These may be associated with diaphoresis, tachypnoea and signs of respiratory distress such as subcostal recession and nasal flaring.

By contrast, older children may have a history of unexplained lethargy and reduced exercise tolerance when compared with their peers for age-specific activities (eg walking up the stairs, playing organised sports). Of course, it is also possible that children with even quite significant congenital heart lesions may be completely asymptomatic and have normal exercise tolerance.

A comprehensive history starts from the antenatal period, looking for potential risk factors of congenital heart disease.

In up to 20% of cases, the condition is directly related to either genetic abnormalities or teratogens, but these factors may not be identified as part of the history.

A family history should be sought of structural cardiac abnormalities and of maternal complications of pregnancy (especially gestational diabetes mellitus), illness during pregnancy (eg infection, although less common these days), prescribed or non-prescribed medications.

- Congenital Heart Disease- Murmurs

1/6 murmur is barely audible;

2/6 audible but soft;

3/6 is easily audible but without a thrill;

4/6 murmur has a thrill;

5/6 is with a thrill and heard with stethoscope hardly touching the chest;

6/6 murmur has a thrill and is audible without the stethoscope on the chest.

- Congenital Heart Disease- Examination

A basic set of observations is an important first step in assessing the child with a murmur. This includes:

- respiratory rate,

- heart rate,

- peripheral saturations and

- blood pressure.

Particular attention should be made to respiratory effort as a sign of cardiac failure.

It is important to examine for any dysmorphic features that may be associated with congenital heart disease (Table 1).

As children can be difficult to examine, it is important to be flexible and opportunistic in approach.

Characterisation of the murmur is important; however, this can be challenging as heart rate is much faster in infants. Innocent murmurs are those arising from increased velocity of blood flow through a structurally normal heart and, typically, are soft, with an intensity ≤2/6*, heard in systole and ejection in character.

They may be continuous in the setting of a venous hum, although these murmurs disappear on lying flat. Conversely, harsh murmurs, those that are pan-systolic, diastolic, or continuous (except venous hums) are pathological. Similarly, murmurs that increase in intensity with either positional changes (eg squatting to standing) or Valsalva manoeuvers are pathological. While of interest, most young children are not cooperative enough to perform these physiological manoeuvers. Furthermore, additional sounds, such as clicks and fourth heart sounds, are, by definition, pathological. With experience, clinicians may evaluate with high sensitivity whether murmurs are innocent or pathological.

Particular attention must be taken to feel for femoral pulses, looking for a significant coarctation, and hepatomegaly.

The internal jugular vein is difficult to see in infants and young children, so clinicians tend to rely on liver size as a marker of elevated central venous pressure.

Oedema is rarely seen in heart failure in children, but if present in the infant, is typically seen in the peri-orbital/scrotal/labial regions; in older children, it is more likely to be pedal in location.

Basal lung crepitations are rarely heard in young children with heart failure.

- Congenital Heart Disease - DDx

The prevalence of congenital heart disease has been reported as up to 1 in 100, with ventricular septal defects being the most common, making up to one-third of these, followed by atrial septal defects, patent ductus arteriosus and pulmonary stenosis.

However, the incidence of severe congenital heart disease requiring expert management early in life is roughly 3 in 1000.

Congenital heart disease can be broadly divided into cyanotic and acyanotic lesions.

- Acyanotic lesions can be further subdivided into

—> left-to-right shunts (Septal defects and patent ductus arteriosus) and

—> obstructive lesions (pulmonary/aortic valve stenosis and coarctation are typical).

- Cyanotic lesions include

—> tetralogy of Fallot,

—> truncus arteriosus,

—> transposition of the great arteries,

—> total anomalous pulmonary venous drainage and

—> more complex single ventricle hearts (eg hypoplastic left heart syndrome).

Trisomy 21 is typically associated with an AVSD.

- Congenital Heart Disease- Atrial-ventricular septal defect

Murmurs may have change over the months post natal because of the natural ongoing fall in pulmonary vascular resistance in the first three months of life and illnesses.

Tachypnoea, increase in work of breathing and hepatomegaly are indicators of an important left-to-right shunt now and should have a fairly prompt cardiology review.

An electrocardiogram (ECG) may be helpful in making the diagnosis of an AVSD with demonstration of a superior axis.

An AVSD can be repaired surgically. This is a semi-elective procedure usually performed in children with Down syndrome at around the age of three to four months to avoid the complications of pulmonary hypertension. While waiting for surgery, medical treatment with

- diuretics,

- with or without an angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor, and a

- high-calorie diet can be commenced.

- Chest pain in children

Chest pain is a very uncommon manifestation of heart disease in children and is much more likely to be musculoskeletal, gastrointestinal or pulmonary in nature.

A thorough history usually confirms the non-cardiac origin of the chest pain. The nature, location and timing of chest pain often provide the aetiology; however, associated features should also be discussed.

In a teenager, it should be possible to elicit whether there are symptomatic palpitations.

A history of palpitations should lead to questioning over how these start and stop (eg abruptly in re-entrant tachycardia), duration, frequency and associated symptoms.

A family history of arrhythmia, sudden death or epilepsy is useful to stratify risk.

Timing and precipitating factors for presyncopal/syncopal episodes are very important to elicit because those with symptoms during exertion or sudden fright may be at higher risk.

- Congestive Heart Failure Hx

You should seek further information about the primary symptom of dyspnoea.

- What is the time-course of its onset?

- How severe are the symptoms?

- Are there other associated symptoms (ie chest pain/discomfort)?

- CHF Examination

Examine to check for signs of oedema and, if present, whether this is affected by body position.

Undertake a respiratory examination and check his vital signs.

Elevated heart rate, low blood pressure and peripheral oedema indicate the need for a cardiovascular investigation for a possible diagnosis of CHF.

- CHF DDx

Differential diagnoses on initial asessment may include respiratory conditions, including

- pulmonary emboli,

- respiratory tract infection,

- pneumonia or

- asthma.

Swollen ankles may indicate nephrotic syndrome.

Further assessments would be to peform cardiac auscultation and a resting ECG.

ECG- left bundle branch block and suggested left ventricular hypertrophy.

Auscultation- A third heart sound

- CHF Inx

Chest X-ray

A CXR is useful in making a diagnosis of heart failure, but a normal result does not exclude the diagnosis. An increase in cardiothoracic ratio of more than 0.50 indicates cardiomegaly.

Trans-thoracic echocardiography

All patients with suspected heart failure should have an echocardiogram. This is the most effective investigation for determining suspected heart failure because of impaired left ventricular (LV) systolic function or other causes. The echocardiogram gives information about:

- LV and right ventricular (RV) size, volumes and wall thickness

- the presence of regional scarring

- LV and RV systolic function – ejection fraction <40% is highly indicative of heart failure. An ejection fraction of 41–49% may be considered borderline heart failure, but does not always indicate that a person has heart failure

- LV thrombus

- LV diastolic function and filling pressures

- left and right atrial size – enlargement is an important manifestation of chronically elevated filling pressure

- valvular structure and function – assessment of the severity of valvular stenosis or incompetence and whether CHF can be explained by the valve lesion

- pulmonary systolic pressure – in most patients this can be estimated by Doppler echo.

Blood tests

- Brain natriuretic peptide (BNP) – an elevated BNP level is helpful in making a diagnosis of heart failure in patients with unexplained dyspnoea, especially when an echocardiogram is not immediately available.

- Full blood evaluation – anaemia may occur in patients with CHF.

- Urea, creatinine and electrolytes – usually normal in mild-to-moderate heart failure, but may become deranged with more severe heart failure, use of diuretics and angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors and renal dysfunction secondary to worsening heart failure.1 It may help to rule out nephrotic syndrome if the values are normal.

- Liver function tests – congestive hepatomegaly results in abnormal liver function tests.

- Thyroid function tests – hyperthyroidism and hypothyroidism are less common causes of heart failure.

- D-dimer testing – to exclude pulmonary emboli.

- CHF Rx

Provide symptomatic relief initially while awaiting a confirmed diagnosis:

- diuretic regime: 40 mg frusemide for three days

- fluid restriction of <1.5 litres/day and salt avoidance.

- avoid alcohol consumption.

Following heart failure diagnosis:

- Initially, prescribe an angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor, titrating as tolerated to the optimal dose.

- Add a heart failure–specific beta blocker, titrating as tolerated to the optimal dose.

- Consider adding spironolactone in the longer term, if there is ongoing fluid overload.

In addition, should be:

- encouraged to weigh himself daily and advised to contact you if his weight increases more than 2 kg over 48 hours

- educated about

- symptoms of fluid overload, which include worsening shortness of breath on exertion, orthopnoea, fatigue and swelling of the ankles

- the importance of medication adherence.

- CHF Management

Medications that exacerbate heart failure should be avoided. These include

- calcium channel blockers,

- non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs,

- tricyclic antidepressants and

- corticosteroids.

Should be referred to a cardiologist, ideally one specialising in the management of heart failure. An urgent referral may be warranted. In the case of clinical deterioration, he should present to an emergency department.

There is also strong evidence that heart failure patients benefit from multidisciplinary management.

This involves coordinated care between different health professionals to support patients in self- management. In Australia, multidisciplinary care can be delivered in a range of settings, including general practice, hospital clinics, community and home-based structured programs, and specialist private practice.

In the medium term (once diagnosis has been established and evidence- based medication initiated), patient should be referred to a supervised cardiac rehabilitation program for exercise rehabilition. Initially, this will involve short bouts of low-to-moderate intensity aerobic exercise, as symptoms allow (the patient should not become so short of breath that they cannot conduct a conversation).

Frequency of exercise sessions (days per week) and duration of exercise bouts should be increased initially before increasing intensity.

In the longer term, patients with CHF will benefit from ongoing, regular aerobic exercise, as well as moderate resistance exercise (weight lifting) involving major muscle groups of the upper and lower body.

Exercise prescription and supervision can be provided by an accredited exercise physiologist or physiotherapist, or a home-based exercise training regimen can be provided.

- CHF Monitoring

Serial echocardiography is not indicated to monitor heart failure unless signs or symptoms change or to monitor the effect of therapeutic interventions.

If there is a significant change in the severity of symptoms, re-assessment of systolic, diastolic or valvular function is appropriate.

Implantable cardioverter defibrillators are indicated in patients with ejection fractions of <35% or survivors of cardiac arrest.

Cardiac resynchronisation therapy with a biventricular pacemaker may provide benefit in patients with a QRS >150 milliseconds.

For patients with end-stage heart failure (New York Heart Association Functional Class III–IV) and refractory to conventional medical management (Table 1), advanced therapies include inotropic medication,

left ventricular assist devices and cardiac transplantation (through an Advanced Heart Failure/Cardiac Transplant Service).

In patients with end-stage heart failure, advance care planning and palliation should be implemented when advanced therapies are not an option.

- CHF Prognosis and Secondary prevention

Survival in patients with heart failure has improved markedly over the past 20 years, with better pharmacological therapy and the widespread use of implantable cardioverter defibrillators in patients at risk of life- threatening arrhythmias.

Among patients aged 60 years, five-year survival is approximately 70% in men and 75% in women; however, prognosis remains unpredictable. With good medical management, many people with mild-to-moderate heart failure survive for extended periods, whereas in other patients, the course of the disease is more aggressive and LV function may deteriorate quickly.

To improve long-term health, lifestyle interventions should be encouraged. These include:

- maintaining weight within the healthy range;

- regular exercise and physical activity;

- abstinence from smoking and use of illicit drugs; and

- avoiding excessive alcohol consumption (patients with alcoholic cardiomyopathy should abstain from alcohol).

Maintenance of blood pressure at low to normal levels is essential. Monitor blood glucose regularly for diabetes or pre-diabetes.