Acute Abdomen Flashcards

What type of pain would someone with appendicitis complain of?

central abdominal pain that moves into the right iliac fossa

Typically, how does someone with appendicitis present?

- tends to be a young person (5 - 40 years old)

- acute onset within 12 - 24 hours

- present with umbilical pain that moves to the right iliac fossa

- nausea and/or vomiting

- diarrhoea or constipation

- fever

What might be present on general inspection and palpation of someone with appendicitis?

- in the early stages there is general pain and peri-umbilical pain on palpation

- in the later stages, the person will often stay very still due to peritonitis

- this occurs after the appendix has ruptured, and the peritoneum has become inflamed

on palpation, there will be right iliac fossa pain

What signs might be present in appendicitis?

- Rovsing’s sign

- Cope’s sign

- Psoas sign

- rebound tenderness

What is Rovsing’s sign?

- pain is greater in the RIF than the LIF when the LIF is pressed

- this is specific to appendicitis

What is Cope’s sign?

- there is pain on passive flexion and internal rotation of the hip

- it indicates irritation to the obturator internus muscle

- the appendix becomes inflamed and enlarged and may come into contact with the obturator internus muscle when this move is performed

What is Psoas sign?

- there is pain on extending the hip

- pain indicates an inflamed appendix overlying the iliopsoas muscles

- this only occurs with retrocaecal appendix

- (as the iliopsoas muscle is retroperioneal)

- this indicates that the inflamed appendix sits behind the caecum

When might rebound tenderness be evident in appendicitis?

What is this?

- this indicates that the infection is involving the peritoneum

- there is pain upon removal of pressure from the abdomen rather than application of pressure to the abdomen

- this is indicative of peritonitis

- there may also be abdominal guarding - the abdominal muscles tense up to avoid pain

What are the investigations involved in appendicitis?

- first line investigation is CT abdomen

- USS can be done if CT is not available

- this will show increased appendix diameter and increased wall enhancement

- bloods - which will show leucocytosis and elevated CRP

What is the most common cause of appendicitis in adults?

- appendicitis results from obstruction of the appendix lumen

- this may be due to a fecalith (hardened lump of faecal matter) that wedges itself within the lumen

- it can also be due to undigested seeds or pinworm infections

What is a common cause of appendicitis in adolescents?

lymphoid hyperplasia

- this involves growth of the lymphoid follicles, which are dense collections of lymphocytes

- these reach their maximum size in adolescence and can obstruct the lumen of the appendix

- when exposed to viral infections or immunisations, the follicles can increase in size

How does obstruction of the lumen of the appendix lead to pain?

- the intestinal mucosa secretes mucus and fluids to keep pathogens from entering the bloodstream and to keep the tissue moist

- even when obstructed, the appendix keeps secreting

- there is a build up of fluid and mucus in the appendix, which increases the pressure

- the appendix gets bigger and physically pushes on afferent visceral nerve fibres nearby, causing pain

Why is there is an increase in serum WBC count in acute appendicitis?

What processes have to occur prior to this for it to occur?

- as there is an obstruction, flora and bacteria in the gut are trapped

- E. coli and bacteroides fragilis

- these bacteria are now free to multiply

- this causes the immune system to produce WBCs, which leads to the build up of pus in the appendix

What happens if the obstruction in the appendix persists past the build-up of pus in the appendix?

- the pressure in the appendix increases even further

- it expands and begins to compress small blood vessels that supply it with blood and oxygen

- without oxygen, the cells in the wall of the appendix become ischaemic and die

- these cells were responsible for secreting mucus and keeping bacteria out, so now the growing colony of bacteria can invade the wall of the appendix

What leads to rupture of the appendix?

What happens if the appendix ruptures?

- as more cells in the wall of the appendix die, it becomes weaker and weaker

- in a small proportion of patients, the appendix wall becomes so weak that it ruptures

- this leads to bacteria entering into the peritoneum and causing peritonitis

- this leads to abdominal guarding and rebound tenderness at McBurney’s point

What is the most common complication of a ruptured appendix?

- formation of a periappendiceal abscess

- this is a collection of fluid and pus around the ruptured appendix

- sometimes smaller subphrenic abscesses can form

- these are below the diaphragm, but above the liver/spleen

What is the treatment for appendicitis?

appendicetomy

- this is surgical removal of the appendix, followed by antibiotics

- if there is an abscess, this must be drained first

What scoring system is used to determine the severity of appendicitis?

Alvarado score

- score of 1 to 4 is discharged

- score of 5 to 6 is observed

- score of 7 to 10 needs surgery

Which antibiotics are given following appendicetomy?

- cefotaxime

-

metronidazole

- this is an anti-anaerobe antibiotic for the gut

What are the 3 possible complications of appendicitis?

- perforation

- appendix abscess

-

appendix mass

- the inflamed appendix becomes covered in omentum and forms a mass

- this tends to occur in older men who avoid coming to the doctors when they get pain

B-hCG test

- the first line investigation in any woman with an abdominal pathology should ALWAYS be a pregnancy test

What is meant by diverticulosis?

- the presence of diverticulae

- these are outpouchings of the colonic mucosa and submucosa throughout the large bowel

-

high pressure in the bowel causes these outpouchings to form

- e.g. chronic constipation

What is meant by diverticulitis?

Which part of the bowel is more commonly affected?

- acute inflammation and infection of the diverticulae

- most commonly affects the sigmoid colon

What is the structure of the large intestine wall like?

What is the difference between a true diverticula and a pseudo-diverticula (false)?

- the wall of the large intestine is made up of 4 layers

- mucosa

- submucosa

- muscle layer

- serosa

- a true diverticula involves all 4 layers of the intestine

- a false (pseudo) diverticula includes only the mucosa and submucosa

- these 2 layers are covered by serosa only, and the muscle layer is not involved

- these are more common

Why do diverticula form?

- they are formed by high pressure within the lumen of the large intestine

-

smooth muscle in the intestinal wall contracts to push food along the bowel

- when it contracts, higher pressures are generated inside the lumen as it “squeezes” air inside

- contractions in someone with diverticula are abnormal

- instead of pressure being distributed evenly throughout the lumen, there are areas of very high pressure during abnormal smooth muscle contraction, which leads to diverticula formation

What is the most common location for diverticula to form and why?

sigmoid colon

- this has the smallest lumen diameter, and so it subject to the highest intraluminal pressures

Does rectal bleeding (haematochezia) occur in diverticulosis and/or diverticulitis?

Why?

- PR bleeding can occur in diverticulosis

- a diverticulum can form where blood vessels traverse the muscle layer, as this point of the wall is weaker

- the blood vessel becomes separated from the intestinal lumen only by mucosa

- it is predisposed to rupture, meaning blood enters the large intestine

- PR bleeding does NOT occur in diverticulitis

- this is because the blood vessels become scarred from inflammation

What genetic conditions and lifestyle factors are associated with an increased risk of diverticular disease?

- anything that increases the stress on the intestinal walls or decreases their strength predisposes to diverticula

-

Marfan syndrome & Ehlers-Danlos are genetic conditions that affect connective tissue

- diverticula can form in the absence of strong connective tissue supporting the intestinal wall

- diets low in fibre and high in fatty foods and red meat increases risk of symptomatic diverticular disease

What symptoms may be present in diverticulosis?

- this is the presence of diverticula and usually has no symptoms

- sometimes there will be vague stomach pain and the diverticula can bleed

- they are often found incidentally on colonoscopy or CT scan

What are the 2 reasons why diverticula may become inflamed and cause diverticulitis?

- if a faecalith becomes lodged in the diverticula (less common)

- due to erosion of the walls of the diverticula from higher luminal pressures

What is the most severe complication of diverticulitis?

- if the diverticula become distended enough, they can rupture and form a fistula

- this is a connection with an adjacent organ or structure

- a colovesicular fistula between the large intestine and the bladder might form, leading to air or stool in the urine

How does someone with acute diverticulitis typically present?

- left iliac fossa pain +/- bloating

- anorexia

- this refers to not eating much

- fever

- nausea & vomiting

- may have bloody stools

- may have urinary symptoms if colovesicular fistula has formed

- e.g. brown urine due to the presence of faeces in the urine

What are the risk factors associated with diverticulitis?

- tends to present in 50 - 70 year olds who have previously been asymptomatic

- low dietary fibre

- smoking

- chronic NSAID use

What would someone look like on general inspection and palpation in acute diverticulitis?

What if they had peritonitis?

Acute diverticulitis:

- tachycardia

- low-grade pyrexia

- LIF tenderness on palpation

Peritonitis:

- this may occur if they have a perforated diverticulum

- they will be lying very still to not aggravate the pain

- on palpation, there will be guarding and rebound tenderness

What is the primary investigation for acute diverticulitis?

What other investigation might be performed if perforation is suspected?

CT abdomen with contrast

- an erect CXR may be performed if there are signs of perforation

- the presence of air under the diaphragm confirms perforation

- inflammation is shown as hyperdense tissue

What investigation might be performed once someone has recovered from diverticulitis?

barium enema +/- flexible sigmoidoscopy / colonoscopy

this is to confirm the presence of chronic diverticulosis

What is the treatment for mild and severe diverticulitis?

Mild / Uncomplicated:

- oral antibiotics (in more severe cases, IV antibiotics are given)

- fluids

- bowel rest (no food / water orally)

Severe:

- bowel resection is performed if there is recurrence / severe cases

- this usually involves Hartmann’s procedure

What is involved in Hartmann’s procedure?

Why is this performed to treat acute diverticulitis?

- this involves emergency / acute removal of a piece of bowel

- this usually involves removal of the sigmoid colon

- this results in formation of an end colostomy and anorectal stump

- an immediate primary anastomosis is not possible due to inflammation and oedema

- when the oedema starts to settle down, gaps will appear in the anastomosis and it will become leaky

What is the treatment for diverticulosis?

- encourage the patient to have a soluble, high-fibre diet

- once the inflammation has settled down from diverticulitis, a primary anastomosis can be formed

What other operation may accompany formation of an anastomosis in distal large bowel cancers (e.g. rectal carcinoma)?

defunctioning loop ileostomy

- this diverts bowel contents away from a distal anastomosis

- this allows it time to rest prior to reversal of the loop ileostomy

What are the possible complications of diverticular disease?

- acute diverticulitis

- faecal peritonitis

- this tends to occur if there is rupture of a diverticulum

- fistula formation

- peri-colic abscess

- colonic obstruction

- perforation

C - diverticulitis

- presence of bloody stools

- she has had blood in the past - bleeding diverticula

- fever

- tenderness in left iliac fossa

- this is the location of the sigmoid colon

- low fibre diet

A - Hartmann’s procedure

- the presence of air under the diaphragm shows perforation

- a primary anastomosis cannot be performed in the acute presentation

What is the definition of a hernia?

What are the 2 major types?

a condition in which part of an organ is displaced and protrudes through the wall of the cavity containing it

- this is often involving the intestine at a weak point in the abdominal wall

- the 2 main types are inguinal and femoral

In what 2 different ways can abdominal hernias be classified?

-

midline hernias

- epigastric hernias

- umbilical hernias

-

groin hernias

- femoral hernias

- inguinal hernias (much more common)

- can also get incisional hernias when abdominal contents herniate through a scar from a previous abdominal surgery

What are the layers of the abdominal wall?

What could cause something to protrude through these layers?

- deepest layer is the visceral peritoneum

- this covers many abdominal organs and lines the peritoneal space

- this layer wraps around to form the parietal peritoneum

- extraperitoneal fat

- transversalis fascia

- muscle layer containing external oblique, internal oblique & transversus abdominis aponeurosis

- fascia

- anything that increases the pressure in the abdominal cavity may result in a sac that forms in the abdominal wall through which organs might protrude

What are the 2 different types of midline hernias and when do they occur?

- a midline hernia occurs when organs protrude through the midline

- an epigastric hernia occurs when organs protrude through the linea alba, between the xiphoid process and the umbilicus

- an umbilical hernia occurs when organs protrude through the umbilicus

What is meant by an inguinal hernia?

What are the 2 openings of the inguinal canal?

- an inguinal hernia occurs when abdominal contents protrude through the inguinal canal

- the deep inguinal ring is an opening in the transversalis muscle fascia

- the superficial inguinal ring is an opening in the external oblique muscle aponeurosis

Why are inguinal hernias much more common in males?

- the inguinal canal is much larger and more prominent in males, which creates a site of weakness in the abdominal wall

- this is due to the testes having to descend further than the ovaries during development, meaning that the processus vaginalis (now obliterated) may remain open

What is meant by an indirect inguinal hernia and why does it occur?

Who tends to be affected by these?

- occurs when the processus vaginalis fails to close after the testes have passed through it

- sometimes called a congenital hernia

- when the processus vaginalis remains open, intestinal contents herniate through BOTH the deep and superficial inguinal rings and into the scrotum

- think “contents herniate INDIRECTLY through the inguinal canal”

- this is more common in infants and children but can be discovered in adulthood

What is meant by a direct inguinal hernia and why does it occur?

Who tends to be affected by this?

- this results from weakness of the transversalis fascia

- sometimes called an acquired hernia

- the abdominal wall gets weaker with age, so these tend to occur in middle-aged and elderly people

- the intestinal contents pass through the external inguinal ring ONLY

- think “contents are herniating DIRECTLY through the abdominal wall”

In which location is a direct inguinal hernia most likely to occur?

When does this happen?

- the transversalis fascia weakens most commonly in the posterior wall of the inguinal canal

- this region is called Hesselbach’s triangle

- hernia through Hesselbach’s triangle occurs as a result of increased abdominal pressure, usually through coughing or heavy lifting

What happens in a femoral hernia?

- occurs when abdominal contents herniate beneath the inguinal ligament and into the femoral canal

- these are less common than inguinal hernias

What is the difference between an uncomplicated hernia and an incarcerated hernia?

- in an uncomplicated hernia, the hernia can be reduced back into the abdomen by pressing on the hernial sac

- this is a pouch of peritoneum that covers the herniating organ

- if the contents of the hernia cannot be pushed back inside the abdomen then this is incarceration

- there is reduced venous and lymphatic flow

- this leads to swelling and oedema of the incarcerated tissue

What is meant by a strangulated hernia?

- if a hernia is incarcerated, eventually the tissue will swell so much that the arterial blood flow to the hernial contents is completely cut off

- this is strangulation and it leads to ischaemia** and **tissue necrosis

How would someone with a hernia typically present?

- small hernias are often asymptomatic

- palpable lump in groin

- pain in the groin

- scrotal swelling (inguinal hernia)

-

nausea & vomiting / fever are signs of incarceration

- incarceration may interrupt passage of contents through the intestines and lead to symptoms of bowel obstruction

- if the hernia appears red, it is likely to be strangulated and there is blood trapped in the hernial sac

- (groin pain and vomiting are red flags)*

What are key features to pick up in the history of someone who could have an inguinal or femoral hernia?

- increasing age

- obesity

- history of chronic constipation

- history of chronic cough

- recent heavy lifting (e.g. gym)

- (obesity, constipation, cough and lifting all increase intra-abdominal pressure)*

Who tends to be more affected by femoral and inguinal hernias?

Which is more likely to become strangulated and which is more likely to need surgery?

- inguinal hernias are the most common hernia in both sexes

- but femoral hernias occur more often in women

- femoral hernias are more commonly strangulated*** and ***surgery is recommended

- femoral hernias affect older people and inguinal hernias affect younger people

What is the defintion of a strangulated hernia?

the compression around the hernia prevents blood flow into the hernial contents causing ischaemia to the tissues and pain

Where is a femoral hernia located and what is often contained within it?

- located lateral and inferior to the pubic tubercle

- often contains omentum

What is the location of the inguinal hernia?

What is often contained within it?

- located superior and medial to the pubic tubercle

- often contains bowel

What are the features that are common to both femoral and inguinal hernias?

What are the signs that they might have become strangulated?

- swells / appears on coughing and may reduce on supination

- both may be reducible on pressure

- signs of strangulation include:

- redness / tender

- colicky abdominal pain

- distension

- vomiting

What are the borders of Hesselbach’s triangle?

What type of hernia is this associated with?

- rectus abdominus

- inferior epigastric vessels

- inguinal ligament

- associated with a direct inguinal hernia that will protrude through this weakness in the abdominal wall

- this tends to occur in older people, weight-lifters and manual labour workers

How can you make a clinical diagnosis of an inguinal hernia and distinguish an indirect from a direct hernia?

- reduce the hernia

-

place your finger over the _deep inguinal ring_

- just above the midpoint of the inguinal ligament

- ask the patient to cough

-

if the hernia reappears, it _CANNOT_ be an _indirect hernia_ (must be direct)

- your finger is blocking the deep inguinal ring so the indirect hernia could not pass through

- if still unsure, an USS can be done to locate the hernia and decide whether it is composed of bowel or omentum

- femoral = omentum

- inguinal = bowel

Which type of hernia is more likely to need surgery?

- femoral hernia needs urgent surgery due to risk of strangulation

- for inguinal hernia, surgery is less urgent

- this tends to be mesh repair or more conservative measures like wearing a corset

What is meant by inflammation of the pancreas?

What are the 2 different types?

- inflammation of the pancreas

- leading to autodigestion of pancreatic tissue by the pancreatic enzymes, resulting in necrosis

- this can occur in either an acute or chronic setting

What is the definition of acute pancreatitis?

sudden inflammation and haemorrhaging of the pancreas due to destruction by its own digestive enzymes (autodigestion)

What are the endocrine and exocrine roles of the pancreas?

Endocrine:

- alpha and beta cells release hormones like insulin and glucagon into the blood

Exocrine:

- acinar cells secrete digestive enzymes into the duodenum

- these break down carbohydrates, proteins and lipids that are also found within the cells of the pancreas

How does the pancreas protect itself from autodigestion normally?

- the acinar cells manufacture inactive forms of digestive enzymes (zymogens)

- zymogens are stored in vesicles (zymogen granules) with protease inhibitors

- this allows for extra protection if the zymogens were to become prematurely active

- the zymogens are released into the pancreatic duct and delivered to the duodenum, where they activated by trypsin

- trypsin comes from the pancreatic zymogen trypsinogen, which is activated by enteropeptidases in the duodenum

What are the 2 main causes of acute pancreatitis?

What is the mechanism behind this?

- early activation of trypsinogen or zymogens causes acute pancreatitis

- this can occur due to injury to the acinar cells

- or due to anything that impairs secretion of zymogens into the duodenum

- the 2 main causes are alcohol and gallstones

What is the mechanism behind how alcohol can cause acute pancreatitis?

- alcohol increases zymogen secretion from acinar cells

- it also decreases fluid and bicarbonate secretion from ductal epithelial cells

- the pancreatic juices become very thick and viscous

- this leads to a plug forming, which blocks the pancreatic ducts

- plug formation leads to pancreatic juices backing up, increasing the pressure within and distending the pancreatic ducts

How can a blocked and distended pancreatic duct lead to acute pancreatitis?

- distended ducts make membrane trafficking become more chaotic

- zymogen granules may fuse with lysosomes, bringing trypsinogen into contact with digestive enzymes

- trypsinogen is converted to active trypsin, which starts the cascade of enzyme activation within the pancreas

- this leads to autodigestion of pancreatic tissue

In what other ways can alcohol contribute to the development of acute pancreatitis?

- alcohol stimulates release of inflammatory cytokines, stimulating an immune response

- neutrophils arriving at the scene release proteases, making the problem worse

- high consumption of alcohol can produce enough reactive oxygen species to overwhelm cellular defences and damage the cells

How can gallstones lead to acute pancreatitis?

- gallstones can block the sphincter of Oddi

- this blocks the release of pancreatic juices

What is liquefactive haemorrhagic necrosis?

How does it occur?

- autodigestion / pancreatic tissue destruction can cause tiny blood vessels to become leaky and sometimes rupture

- extra fluid causes swelling and oedema of the pancreas

- this can activate lipases which digest the peripancreatic fat

- this is the fat surrounding the pancreas

- digestion and bleeding can liquefy pancreatic tissue

- this is liquefactive haemorrhagic necrosis

What is a pancreatic pseudocyst and how does it form?

What symptoms might be seen with this?

- fibrous tissue surrounds the liquefactive necrotic tissue of the pancreas

- this forms a cavity that fills with pancreatic juices

- typical symptoms include abdominal pain, loss of appetite and palpable abdominal mass following a bout of pancreatitis

-

serum amylase, bilirubin and lipase may be raised

- the best way to image a cyst is with abdominal CT

What happens if the pancreatic pseudo-cyst becomes infected?

- it forms a pancreatic abscess

- it is usually infected by E. coli

- this presents with the same symptoms, with additional fever and high WCC

How does someone with acute pancreatitis typically present?

- intense epigastric pain that may radiate to the back

- pain is worse on movement

- pain is relieved when sitting forwards

What is the mnemonic to remember the causes of acute pancreatitis?

I GET SMASHED

- I - idiopathic

- G - gallstones

- E - ethanol

- T - trauma

- S - steroids

- M - mumps infection

- A - autoimmune

- S - scorpion venom

- H - hypercalcaemia, hyperlipidaemia, hyperparathyroidism

- E - ERCP

- D - drugs (thiazides)

On examination, what signs might be present in acute pancreatitis?

- epigastric tenderness

- fever

- reduced bowel sounds

- shock, tachycardia, tachypnoea

- Cullen’s sign & Grey-Turner’s sign

What are Cullen’s sign and Grey-Turner’s sign and why do they occur?

- they occur due to intra-abdominal bleeding from pancreatic inflammation

- Cullen’s sign is bruising around the umbilicus

-

Grey-Turner’s sign is bruising in the flanks

- remember “you have to TURN over to see it”

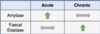

What blood tests will be deranged in acute pancreatitis?

- increase in serum digestive enzymes, including amylase and lipase

amylase is not very specific

- it will be raised in any cause of acute abdomen, including pancreatitis

lipase is more specific

-

hypocalcaemia occurs in acute pancreatitis

- this occurs as fat necrosis consumes calcium

What other investigations may be performed in acute pancreatitis?

-

serum amylase

- should be > 3x upper limit of normal

- serum lipase

- USS to look for the cause (i.e. gallstones)

- erect CXR and CT abdomen

- CT will show inflammation, necrosis and pseudocysts

Why can acute pancreatitis lead to hypovolaemic shock and bleeding?

What is the most severe complication of acute pancreatitis?

- haemorrhage from a damaged blood vessel can lead to shock

- there may be systemic activation of blood coagulation factors (DIC)

this leads to small blood clots forming all over the body, using up clotting factors and making it easier to bleed

- massive pancreatic inflammation can lead to acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS)

- this makes it difficult to breath

How can the Modified Glasgow Score be used to determine the severity of pancreatitis?

- a score of > 3 indicates severe pancreatitis

- P - pO2 < 7.9 kPa

- A - age > 55 years

- N - neutrophils > 15 x 109 / L

- C - calcium < 2 mmol / L

- R - renal function

- measured by urea > 16 mmol / L

- E - enzymes

- LDH > 600 U / L or AST > 200 U / L

- A - albumin < 32 g / L

- S - sugar > 10 mmol

How do you expect serum calcium to change in acute pancreatitis?

What would normal calcium suggest?

- serum calcium drops in acute pancreatitis due to sequestering of free Ca2+ by free fatty acids

- very low Ca2+ has worst prognosis

- normal Ca2+ supports an aetiology of hypercalcaemia

What is involved in the medical and surgical management of acute pancreatitis?

- supportive management with fluids and analgesia

- enzyme supplementation

- diabetes medications

- if someone becomes insufficient (i.e. cannot produce sufficient insulin)

- ERCP may be performed to remove a gallstone if present

What is meant by chronic pancreatitis?

How is it different to acute pancreatitis?

Acute pancreatitis:

- involves sudden inflammation of the pancreas caused by digestion by its own enzymes (autodigestion)

- generally is reversible

Chronic pancreatitis:

- involves persistent inflammation of the pancreas caused by irreversible changes to pancreatic structure

- this involves fibrosis, atrophy and calcification

- usually caused by recurrent bouts of acute pancreatitis

What are the most common causes of chronic pancreatitis?

- it is caused by recurrent bouts of acute pancreatitis

- this is most commonly due to alcohol

- trauma to the pancreas

- pancreatic tumours

-

cystic fibrosis

- this is the most common cause of chronic pancreatitis in children

How can cystic fibrosis cause pancreatitis?

- there is a mutation in the CFTR gene, which encodes an ion transporter

- there is disruption to ion transport

- this leads to pancreatic secretions becoming thick / sticky

- viscous secretions will obstruct / block pancreatic ducts

How can repeated bouts of acute pancreatitis progress to chronic pancreatitis?

- with each bout, there is potential for duct dilatation and damage to pancreatic tissue

- as part of the subsequent healing process, pancreatic stellate cells** lay down **fibrotic tissue

- fibrotic tissue causes stenosis (narrowing) of the ducts

- there is also acinar cell atrophy

-

calcium deposits of various sizes can accumulate on the protein plugs that have already formed within the ducts

- this only happens in some causes - such as alcoholic acute pancreatitis

Why can early diagnosis of chronic pancreatitis be challenging?

What is the most common presenting symptom?

- continuous or intense intermittent epigastric pain that may radiate to the back

- this is usually related to eating meals

- it tends to last for several hours

- the pain is relieved on sitting forwards

- in acute pancreatitis, there would be elevated serum amylase and lipase

in chronic pancreatitis, there may not be enough healthy pancreatic tissue to make these enzymes

serum amylase / lipase is NORMAL in chronic states

What imaging investigations are performed to diagnose chronic pancreatitis?

- abdominal X-ray may show calcifications within the pancreas

-

ERCP can be performed to visualise the pancreatic ducts

- this will show a “chain of lakes” pattern due to alternating stenosis and dilatation of the ducts

What marker can be used to distinguish acute and chronic pancreatitis?

faecal elastase

- faecal elastase will be raised in chronic pancreatitis

- it will be normal in acute pancreatitis

-

serum amylase*** will be raised in ***acute pancreatitis

- it will be normal in chronic pancreatitis

As chronic pancreatitis progresses, what signs might someone with pancreatic insufficiency show?

Why does this happen?

- acinar cells become impaired and produce fewer digestive enzymes

- patient has trouble absorbing food / dietary fats, leading to weight loss** and **deficiency of fat-soluble vitamins

- the fat-soluble vitamins are A, D, E and K

- fat passes through the intestines without being digested, leading to greasy, foul-smelling stools

- this is steatorrhoea

What condition can develop as a long-term consequence of chronic pancreatitis?

diabetes mellitus

- recurrent inflammation begins to damage the alpha and beta cells of the pancreas

- this impairs insulin secretion

What is involved in the treatment of chronic pancreatitis?

- treatment mainly involves controlling pain / risk factors

- drinking less alcohol

- eating less meat

- losing weight

- pancreatic enzyme replacement / nutritional supplements are given in pancreatic insufficiency

- diabetes medications are given if necessary

What is meant by bowel obstruction?

What are the 2 categories of causes?

- when the normal flow of contents moving through the intestines is interrupted

Mechanical Causes:

- there is an actual blockage in the large or small intestine

- this blockage can be partial or complete

Functional Causes:

- this is causes by disruption to peristalsis

What is the difference between partial and complete bowel obstruction?

Partial obstruction:

- gas or liquid stool can pass through the point of narrowing

Complete obstruction:

- absolutely nothing can pass through the point of narrowing

What are the mechanical causes of small and large bowel obstruction?

Small bowel obstruction:

- post-operative adhesions

- scar tissue that forms after surgery can form fibrous bands that cause organs to attach to the surgical site or other organs

- the lumen of the bowel can become pinched tight in some locations

- hernias

Large bowel obstruction:

- volvulus

- a loop of intestine twists around on itself, kinking off the lumen

- a volvulus can occur around a mass - e.g. colorectal cancer

Both:

- ingestion of a foreign body

- intussusception

- inflammatory bowel disease - which causes strictures & adhesions

What are the potential functional causes of bowel obstruction?

- anything that reduces smooth muscle contractility / peristalsis

- post-operative ileus

- transient paralysis of the smooth muscle following surgery

- hypothyroidism

- inflammation and infection

- electrolyte abnormalitites

- e.g. hypokalaemia, hypercalcaemia

- some medications - e.g. opioids

How can oedema and ischaemia result from bowel obstruction?

- proximal to the obstruction, gas and stools start to accumulate

- this leads to dilatation of the bowel and abdominal distension

- as pressure within the bowel lumen increases, intenstinal contents will compress blood and lymphatic vessels within the intestinal wall

- veins and lymphatics are compressed first as they have weaker walls

- increased pressure within these vessels pushes fluid into the surrounding area causing mucosal oedema

- if the pressure in the lumen continues to increase, the arteries can become compressed

- this leads to reduced blood flow to the intestinal wall (ischaemia)

How can bowel ischaemia and hypoxia lead to damaged capillaries?

- hypoxia is accompanied by production of reactive oxygen species

- these damage mucosal cells, leading to cell death / mucosal infarction

- capillaries within the intestinal wall rupture, leading to blood entering the intestinal lumen

What happens once blood enters the intestinal lumen?

- the presence of blood and stool in the lumen acts as a nutritional supply for gut bacteria

- gut bacteria multiply rapidly

- gut bacteria enter the intestinal wall

- macrophages rush into the intestinal wall and release inflammatory cytokines

- cytokines increase blood vessel permeability, which increases mucosal oedema, inflammation and damage

What are the consequences in bowel obstruction when inflammatory cytokines have increased blood vessel permeability?

- there is increased mucosal oedema, inflammation and damage

- the overall result is compromised ability of the mucosa to absorb food and water

- this leads to dehydration and loss of electrolytes

How can perforation result from bowel obstruction?

- if pressure within the bowel lumen becomes high enough, it can lead to compression of large arteries

- bowel ischaemia / infarction extends from just the mucosa to all layers of the bowel wall

- this is transmural infarction

- transmural infarction can lead to perforation

- bacteria within the bowel lumen leak into the peritoneal cavity and cause peritonitis

How can peritonitis lead to sepsis?

- the layers of the peritoneum are highly vascularised

- large numbers of bacteria enter the bloodstream, causing a massive inflammatory response

- this is sepsis

- blood vessels throughout the body become “leaky”, allowing cells and fluid to leak into the interstitial space

- this reduces blood volume and blood pressure

- there is less blood and oxygen reaching vital organs, which is shock

What are the typical symptoms of bowel obstruction?

-

vomiting

- this is more common in small bowel obstruction

- abdominal distension

- constipation

- diffuse / cramping abdominal pain

How can you tell the difference in symptoms of complete and partial bowel obstruction?

Partial obstruction:

- symptoms come on more gradually and are milder

- e.g. abdominal pain after meals, constipation

Complete obstruction:

- symptoms tend to come on very suddenly

- there is absolute constipation

- absolutely nothing can pass - not even gas / liquid stool

How are the symptoms different in small and large bowel obstruction?

How might you know if there has been a perforation?

Small bowel:

- vomiting is more common

- pain tends to be periumbilical (around bellybutton)

- bouts of crampy intermittent abdominal pain that last for a few minutes at a time

Large bowel:

- vomiting is less common

- pain tends to be lower down in the abdomen

- bouts of pain tend to be less frequent, but last for longer

Perforation:

- when there is progression from vague / crampy pains to more constant / focal pains

- this indicates peritoneal irritation due to perforation

What are key things to pick up in the history of someone with a bowel obstruction?

-

malignancy history

- colorectal cancer can cause volvulus

- hernia history

- surgical history (risk of adhesions)

How can bowel obstruction affect breathing?

- abdominal distension can push on the diaphragm and make it more difficult for the lungs to expand

- this leads to respiratory distress

- patient may present with shortness of breath, tachypnoea and cyanosis

What might you see on general inspection and auscultation in bowel obstruction?

- high-pitched, tinkling bowel sounds suggest mechanical obstruction

- complete absence of bowel sounds suggests functional obstruction

- abdominal distension

- pyrexia / sweating - this is more prevalent if there is a perforation

What investigations are performed if bowel obstruction is suspected?

-

abdominal X-ray

- looking for signs of volvulus and/or Rigler’s sign

- CT abdomen with contrast

- abdominal USS if CT is contraindicated

- e.g. in pregnancy / contrast allergy

- bloods

- FBC and crossmatch - in case of perforation

How can you tell the difference between large bowel and small bowel on AXR?

-

valvulae conniventes are seen in the small bowel

- these are lines that transect the entire bowel

-

haustra are seen in the large bowel

- these do not transect the entire bowel

How do you tell the difference between caecal and sigmoid volvulus on AXR?

-

caecal volvulus is represented by the “embryo”** or **“comma” sign

- formed from the caecum folding up in RIF

- sigmoid volvulus is represented by the coffee bean sign

What is Rigler’s sign?

- if there is air present on both sides of the bowel wall then this indicates perforation

- also known as the double-wall sign

- there is gas outlining both sides of the bowel wall

- gas within the bowel lumen and gas within the peritoneum

What are the treatment options for bowel obstruction?

- generally, bowel obstructions resolve on their own so treatment focuses on relieving symptoms

- IV fluids

- nasogastric suction

- “drip and suck” to remove gas / liquid from the stomach that has accumulated

- if symptoms do not improve, or there is perforation, then surgery is performed

What is meant by intestinal ischaemia?

What are the 2 different types?

- reduction in blood flow to the intestine, resulting in ischaemia of the bowel wall

- if it affects the small bowel, it is mesenteric ischaemia

- if it affects the large bowel, it is ischaemic colitis

- this leads to infarction when part of the intestinal wall necroses/dies

What is the main source of blood to the small intestine?

What type of blood supply exists to try and prevent small bowel ischaemia?

- blood supply mainly comes from the superior mesenteric artery

- branches of this artery spread through the mesentery (mesenteric arteries)

- mesenteric arteries penetrate the submucosa and branch into arterioles

- small intestine has a high demand for oxygen and nutrients to sustain digestion, so it is susceptible to ischaemia

- mesenteric arteries branch and reconnect at points forming a collateral circulation

- if blood flow is reduced in one pathway, the tissue can still receive blood via another pathway

When does small bowel infarction occur?

- when there is significant reduction in blood flow to the small intestine

- this reduces the blood pressure meaning that there is insufficient blood flow throughout the collateral circulation

- this initiates ischaemic injury in a wide region of tissue

What is meant by reperfusion injury?

- reperfusion injury occurs when blood flow returns to ischaemic tissue

- influx of oxygen into an already damaged cell can increase oxidative stress and cause further cell damage

- damaged /ischaemic cells release reactive oxygen species, which stimulate an immune response

- immune cells remove damaged/dead cells and release cytokines

- cytokines cause blood vessels to become more permeable, resulting in bowel oedema

What layers of the bowel are affected in mesenteric ischaemia?

How do symptoms range in severity?

- mesenteric ischaemia becomes more severe as it extends from a mucosal infarct to a transmural infarct

- it goes from only affecting the mucosa to affecting all the layers of the bowel wall

- early-on, ischaemia causes ileus

- this is where the bowel stops working

- food lingers in the bowel and doesn’t get pushed along

- severe damage can cause a break in the epithelial lining of the bowel, allowing bacteria in the lumen to enter blood vessels within the bowel wall

- bacteria can pass through the wall into the peritoneal space, causing bacterial peritonitis

- they can also pass from the peritoneal space into lymphatics and blood vessels

- if bacteria enter the bloodstream, this can lead to septic shock

- this involves hypoperfusion of organs throughout the body

What are the occlusive causes of mesenteric ischaemia?

What type of infarct does this usually cause?

- this involves a physical blockage that prevents blood flow through the vasculature

- usually causes a transmural infarct

-

thrombus formation in superior mesenteric artery or vein

- this leads to thrombosis and occlusion of the vessel

-

thromboembolism occluding superior mesenteric artery

- part of a blood clot has broken off, travelled through the bloodstream and lodged in SMA

- tumour, hernia, volvulus or intussusception (telescoping of bowel) can physically compress the vascualture and occlude blood flow

What are the non-occlusive causes of mesenteric ischaemia?

What type of infarct does this usually cause?

- non-occlusive causes are related to systemic decreases in blood flow

- this usually leads to mucosal infarcts

- hypovolaemia due to severe haemorrhage or dehydration

-

low cardiac output state

- e.g. after an MI

What is the key triad of symptoms associated with mesenteric ischaemia?

- sudden, diffuse abdominal pain

- shock

- normal abdominal examination

What are the typical symptoms of mesenteric ischaemia?

- ischaemia causes sudden, severe abdominal pain

- the abdomen is normal on examination and soft

- infarction develops after 12 hours and causes vomiting and bloody diarrhoea (sometimes)

- over time, the abdomen becomes distended and bowel sounds stop as the bowel stops moving

What are the signs that mesenteric ischaemia has lead to sepsis or peritoneal inflammation?

- signs of sepsis include hypotension, tachycardia, tachypnoea and fever

- fluid accumulating in the abdomen leads to signs of peritoneal inflammation

- these are rebound tenderness and guarding

What is involved in the investigations for mesenteric ischaemia?

- AXR and CT abdomen

- to look for perforation, megacolon and dilation of intestine

- ABG shows lactic acidosis

- CT angiography

- ECG to look for signs of AF

- colonoscopy

Does mesenteric ischaemia tend to be more occlusive or non-occlusive?

What are key risk factors to pick up from the history?

- tends to be more occlusive with sudden, severe symptoms

- risk factors include old age and cardiovascular disease

- risk factors for occlusive causes include

- AF

- cocaine use

- smoking

- risk factors for non-occlusive causes is trauma

What might be seen on abdominal CT and angiography in mesenteric ischaemia?

- abdominal CT shows bowel dilatation and bowel wall thickening from oedema/inflammation

- it can also show intestinal pneumatosis (air in bowel wall)

- CT angiography is used to visualise blood flow through the small intestine

What is involved in the treatment for occlusive and non-occlusive causes mesenteric ischaemia?

- occlusive causes require thrombectomy or thrombolysis

- this involves dissolving a blood clot or re-establishing blood flow through surgery

- non-occlusive causes are treated with fluid resuscitation

- if there is gangrene (ischaemic death of the bowel) then a laparotomy is required

- this requires surgical resection of the infarcted tissue

What are the common symptoms of ischaemic colitis?

- this presents with a much more chronic picture

- transient gut claudication

- PR bleeding

- post-prandial abdominal pain (after eating)

-

weight loss

- less calories are being absorbed from food

What is the blood supply to the large intestine?

Which location is most commonly affected by ischaemic colitis?

- the superior mesenteric artery supplies from the 2nd part of the duodenum up to the splenic flexure

- the inferior mesenteric artery supplies the rest of the colon from the splenic flexure

- if there is hypovolaemia, the splenic flexure will be affected first

- this is due to crossover of blood supply from SMA to IMA

- this is known as Griffith’s point

Does ischaemic colitis tend to be more occlusive or non-occlusive in nature?

- it is more commonly non-occlusive

- symptoms typically involve transient claudication

- treatment is usually conservative with fluids and bowel rest

What are key factors to take from the history of someone presenting with ischaemic colitis?

- old age

- cardiovascular disease

Occlusive causes:

- atrial fibrillation

- smoking

- cocaine use

Non-occlusive causes:

- history of trauma

What is involved in the management of ischaemic colitis?

- management is mainly supportive with IV fluids

-

drip and suck is performed if there is an ileus

- an ileus occurs when the bowel stops moving

- this can cause an obstructive picture (pseudo-obstruction)

- if it is more severe and there is gangrene (areas of infarction) then laparotomy is performed