Reading 25 Risk Management Flashcards

Risk management is…

Risk management is a process involving:

- the identification of exposures to risk,

- the establishment of appropriate ranges for exposures (given a clear understanding of an entity’s objectives and constraints),

- the continuous measurement of these exposures (either present or contemplated), and

- the execution of appropriate adjustments whenever exposure levels fall outside of target ranges.

The process is continuous and may require alterations in any of these activities to reflect new policies, preferences, and information.

!A process is continuous and subject to evaluation and revision.

Is it possible to operate a successful business or investment program without taking risks?

What exactlty kind of risks the companies should hedge?

It is nearly impossible to operate a successful business or investment program without taking risks.

Companies that succeed in doing the activities they should be able to do well, however, cannot afford to fail overall because of activities in which they have no expertise. Accordingly, many companies hedge risks that arise from areas in which they have no expertise or comparative advantage.

If σ is an annual standard deviation and r is annual return, what are monthly standard deviation and return?

σ/(12)0,5

r/12

Qualities of a good ERM?

- Good ERM prectice requires that an individual or group that is independent of the trading function monitor and independently value the positions taken by traders.

- Simply adding VAR estimates from different trading teams together overlooks any diversification effects that may be present, unless the returns of the three teams are perfectly correlated

- Effective risk governance requires that the back office be fully independent from the front office, so as to provide a check on the accuracy of information and to prevent collusion.

- Effective ERM system always feature centralized data warehouses and store all pertinent risk information in a technologically efficient manner.

How many weeks in a year?

52

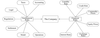

Risk governance, governance structure, ERM

The process of setting overall policies and standards in risk management is called risk governance. Risk governance involves choices of governance structure, infrastructure, reporting, and methodology. The quality of risk governance can be judged by its transparency, accountability, effectiveness (achieving objectives), and efficiency (economy in the use of resources to achieve objectives).

Governance structure: organizations must determine whether they wish their risk management efforts to be centralized or decentralized.

- Under a centralized risk management system, a company has a single risk management group that monitors and ultimately controls all of the organization’s risk-taking activities.

- By contrast, a decentralized system places risk management responsibility on individual business unit managers. In a decentralized approach, each unit calculates and reports its exposures independently. Decentralization has the advantage of allowing the people closer to the actual risk taking to more directly manage it. Centralization permits economies of scale and allows a company to recognize the offsetting nature of distinct exposures that an enterprise might assume in its day-to-day operations.

- even when exposures to a single risk factor do not directly offset one another, enterprise-level risk estimates may be lower than those derived from individual units because of the risk-mitigating benefits of diversification

- centralized risk management puts the responsibility on a level closer to senior management, where we have argued it belongs. It gives an overall picture of the company’s risk position, and ultimately, the overall picture is what counts. This centralized type of risk management is now called enterprise risk management (ERM) or sometimes firmwide risk management because its distinguishing feature is a firmwide or across-enterprise perspective.

- the risk management system of a company that chooses a decentralized risk management approach requires a mechanism by which senior managers can inform themselves about the enterprise’s overall risk exposures.

Effective risk governance:

- trading function vs. risk management function?

- back office vs. the front office?

Regardless of the risk governance approach chosen, effective risk governance for investment firms demands that the trading function be separated from the risk management function.

Effective risk governance for an investment firm also requires that the back office be fully independent from the front office, so as to provide a check on the accuracy of information and to forestall collusion. (The back office is concerned with transaction processing, record keeping, regulatory compliance, and other administrative functions; the front office is concerned with trading and sales.) Besides being independent, the back office of an investment firm must have a high level of competence, training, and knowledge because failed trades, errors, and over-sights can lead to significant losses that may be amplified by leverage. The back office must effectively coordinate with external service suppliers, such as the firm’s global custodian.

What steps typically incorporates an effective ERM system?

An effective ERM system typically incorporates the following steps:

- Identify each risk factor to which the company is exposed.

- Quantify each exposure’s size in money terms.

- Map these inputs into a risk estimation calculation.

- Identify overall risk exposures as well as the contribution to overall risk deriving from each risk factor.

- Set up a process to report on these risks periodically to senior management, who will set up a committee of division heads and executives to determine capital allocations, risk limits, and risk management policies.

- Monitor compliance with policies and risk limits.

Effective ERM systems always feature centralized data warehouses, where a company stores all pertinent risk information, including position and market data, in a technologically efficient manner.

The source of risk?

Market Risk

Market risk is the risk associated with interest rates, exchange rates, stock prices, and commodity prices. It is linked to supply and demand in various marketplaces.

One set of market risk takers with special requirements for market risk are defined-benefit (DB) pension funds, which manage retirement assets generally under strict regulatory regimes. Pension fund risk management necessarily concerns itself with funding the stream of promised payments to pension plan participants. Therefore, a DB plan must measure its market exposures not purely on the basis of its assets but also in terms of the risks of pension assets in relation to liabilities.

Credit Risk

Credit risk is the risk of loss caused by a counterparty or debtor’s failure to make a promised payment. This definition reflects a traditional binary concept of credit risk, by and large embodied by default risk (i.e., the risk of loss associated with the nonperformance of a debtor or counterparty). For the last several years, however, credit markets have taken on more and more of the characteristics typically associated with full-scale trading markets. As this pattern has developed, the lines between credit risk and market risk have blurred as markets for credit derivatives have developed.

Liquidity risk

Liquidity risk is the risk that a financial instrument cannot be purchased or sold without a significant concession in price because of the market’s potential inability to efficiently accommodate the desired trading size.

For traded securities, the size of the bid–ask spread (the spread between the bid and ask prices), stated as a proportion of security price, is frequently used as an indicator of liquidity.

However, bid–ask quotations apply only to specified, usually small size, trades, and are thus an imprecise measure of liquidity risk.

One of the best ways to measure liquidity is through the monitoring of transaction volumes, with the obvious rule of thumb being that the greater the average transaction volume, the more liquid the instrument in question is likely to be.

Operational risk

Operational risk, sometimes called operations risk, is the risk of loss from failures in a company’s systems and procedures or from external events. These risks can arise from computer breakdowns (including bugs, viruses, and hardware problems), human error, and events completely outside of companies’ control, including “acts of God” and terrorist actions.

Model Risk

Model risk is the risk that a model is incorrect or misapplied; in investments, it often refers to valuation models.

Settlement (Herstatt) Risk

Settlement risk as the risk that one party could be in the process of paying the counterparty while the counterparty is declaring bankruptcy.

- All transactions on the exchange take place between an exchange member and the central counterparty, which removes settlement risk from the transaction.

-

OTC markets, including those for bonds and derivatives, do not rely on a clearing house. Instead, they effect settlement through the execution of agreements between the actual counterparties to the transaction. Netting arrangements, used in interest rate swaps and certain other derivatives, can reduce settlement risk.

*

Regulatory Risk

Regulatory risk is the risk associated with the uncertainty of how a transaction will be regulated or with the potential for regulations to change.

- Regulation is a source of uncertainty. Regulated markets are always subject to the risk that the existing regulatory regime will become more onerous, more restrictive, or more costly. Unregulated markets face the risk of becoming regulated, thereby imposing costs and restrictions where none existed previously. Regulatory risk is difficult to estimate because laws are written by politicians and regulations are written by civil servants;

- Regulatory risk often arises from the arbitrage nature of derivatives and structured transactions. For example, a long position in stock accompanied by borrowing can replicate a forward contract or a futures contract. Stocks are regulated by securities regulators, and loans are typically regulated by banking oversight entities. Forward contracts are essentially unregulated. Futures contracts are regulated at the federal level in most countries, but not always by the same agency that regulates the stock market.

Legal/Contract Risk

Legal/contract risk: the possibility of loss arising from the legal system’s failure to enforce a contract in which an enterprise has a financial stake.

Derivative transactions often are arranged by a dealer acting as a principal. The legal system has upheld many claims against dealers.

Tax Risk

Tax risk arises because of the uncertainty associated with tax laws. Tax law covering the ownership and transaction of financial instruments can be extremely complex, and the taxation of derivatives transactions is an area of even more confusion and uncertainty. Tax rulings clarify these matters on occasion, but on other occasions, they confuse them further.

We noted, in discussing regulatory risk, that equivalent combinations of financial instruments are not always regulated the same way. Likewise, equivalent combinations of financial instruments are not always subject to identical tax treatment. This fact creates a tremendous burden of inconsistency and confusion, but on occasion the opportunity arises for arbitrage gains, although the tax authorities often quickly close such opportunities.

Accounting Risk

Accounting risk arises from uncertainty about how a transaction should be recorded and the potential for accounting rules and regulations to change.

- The law demands accurate accounting statements, and inaccurate financial reporting can subject corporations and their principals to civil and criminal litigation for fraud. In addition, the market punishes companies that do not provide accurate accounting statements.

- Confusion over the proper accounting for derivatives gives rise to accounting as a source of risk. As with regulatory and tax risk, sometimes equivalent combinations of derivatives are not accounted for uniformly. The accounting profession typically moves to close such loopholes, but it does not move quickly and certainly does not keep pace with the pace of innovation in financial engineering, so problems nearly always remain.

Sovereign and Political Risks

- Sovereign risk is a form of credit risk in which the borrower is the government of a sovereign nation. Like other forms of credit risk, it has a current and a potential component, and like other forms, its magnitude has two components: the likelihood of default and the estimated recovery rate.

- Political risk is associated with changes in the political environment. Political risk can take many forms, both overt (e.g., the replacement of a pro-capitalist regime with one less so) and subtle (e.g., the potential impact of a change in party control in a developed nation), and it exists in every jurisdiction where financial instruments trade.

Other Risks

Other Risks:

- ESG risk

- Performance netting risk

- Settlement netting risk

Risk management is best addressed?

- daily

- quarterly

- monthly

Risk management is a continuous process; therefore addressing it more frequently is better.

ESG risk

ESG risk is the risk to a company’s market valuation resulting from environmental, social, and governance factors. Environmental risk is created by the operational decisions made by the company managers, including decisions concerning the products and services to offer and the processes to use in producing those products and services. Environmental damage may lead to a variety of negative financial and other consequences. Social risk derives from the company’s various policies and practices regarding human resources, contractual arrangements, and the workplace. Liability from discriminatory workplace policies and the disruption of business resulting from labor strikes are examples of this type of risk. Flaws in corporate governance policies and procedures increase governance risk, with direct and material effects on a company’s value in the marketplace.

Performance netting risk

Performance netting risk, which applies to entities that fund more than one strategy, is the potential for loss resulting from the failure of fees based on net performance to fully cover contractual payout obligations to individual portfolio managers that have positive performance when other portfolio managers have losses and when there are asymmetric incentive fee arrangements with the portfolio managers.

Consider a hedge fund that charges a 20 percent incentive fee of any positive returns and funds two strategies equally, each managed by independent portfolio managers (call them Portfolio Managers A and B). The hedge fund pays Portfolio Managers A and B 10 percent of any gains they achieve. Now assume that in a given year, Portfolio Manager A makes $10 million and Portfolio Manager B loses the same amount. The net incentive fee to the hedge fund is zero because it has generated zero returns. Unless otherwise negotiated, however (and such clauses are rare), the hedge fund remains obligated to pay Portfolio Manager A $1 million. As a result, the hedge fund company has incurred a loss, despite breaking even overall in terms of returns.

Performance netting risk applies not just to hedge funds but also to banks’ and broker/dealers’ trading desks, commodity trading advisors, and indeed, to any environment in which individuals have asymmetric incentive fee arrangements but the entity or unit responsible for paying the fees is compensated on the basis of net results.