What's the most important goal of any teacher? To help students learn more—and actually retain what they've learned.

There are countless teaching methods out there, but they all tend to fall into two broad categories: passive studying and active studying. The difference between the two can determine whether students truly master a subject or just momentarily remember it for a test.

At Brainscape, we’ve gathered feedback from thousands of educators using our adaptive flashcard platform to see which strategies actually improve long-term retention. In this article, we’ll explore the key differences between passive and active learning—and how you can design assessments that reinforce deeper, more lasting knowledge.

Passive vs. Active Approaches for Teaching

Every subject needs a testing method. We have proven since the 70s that not everyone learns at the same pace, uses the same techniques, or will respond equally to testing strategies. It's vital to understand which approaches are out there and how they differ. We're focusing on two big ones in this article: active vs. passive approaches.

What is Passive Studying?

Passive studying usually involves a one-way effort from the students. They absorb information by consuming lectures, textbooks, presentations, etc. Passive testing strategies generally focus on recognition.

The majority of leading quiz apps test for recognition, typically in the form of multiple-choice tests. They ask you a question, and they present you a set of multiple choices (or matching options) in which students simply choose the answer from a list.

While such forms of testing can be convenient for assessment, they are ineffective for testing the knowledge of your students since the activity is so passive.

Moreover, passive approaches often suffer from little motivation from the students to really learn the content. Why memorize when you could recognize?

In contrast, active learning requires students to interact with knowledge and even with other students, increasing engagement and deep learning.

What is Active Studying?

Active studying, on the other hand, involves active participation by the student. It forces full engagement and promotes critical thinking about certain topics. Active testing strategies focus more on the production of knowledge by the students, using essays, in-class discussions, hands-on experiments, or even activities such as making and studying flashcards. The learning and testing become much more about knowing the material rather than passively recognizing it.

Such forms of testing are not only a lot more flexible but are also focused on cementing the knowledge rather than just testing for it. The goal of most tests is to ensure that students retain the knowledge, and active strategies are ideal for consolidation.

Use an Active Approach to Improve Students' Knowledge Retention

A fundamental concept that is used in active approaches to teaching and learning is active recall: the ability to remember a concept from scratch without assistance. Here, students actively search their memory to produce the answer rather than passively recognizing.

The literature shows that active recall is tremendously effective, much more than recognition, even if the goal is to perform well on a multiple-choice test. The U.S. Department of Education also strongly recommends that students should actively recall specific information in order to “directly promote learning and help students remember things longer”.

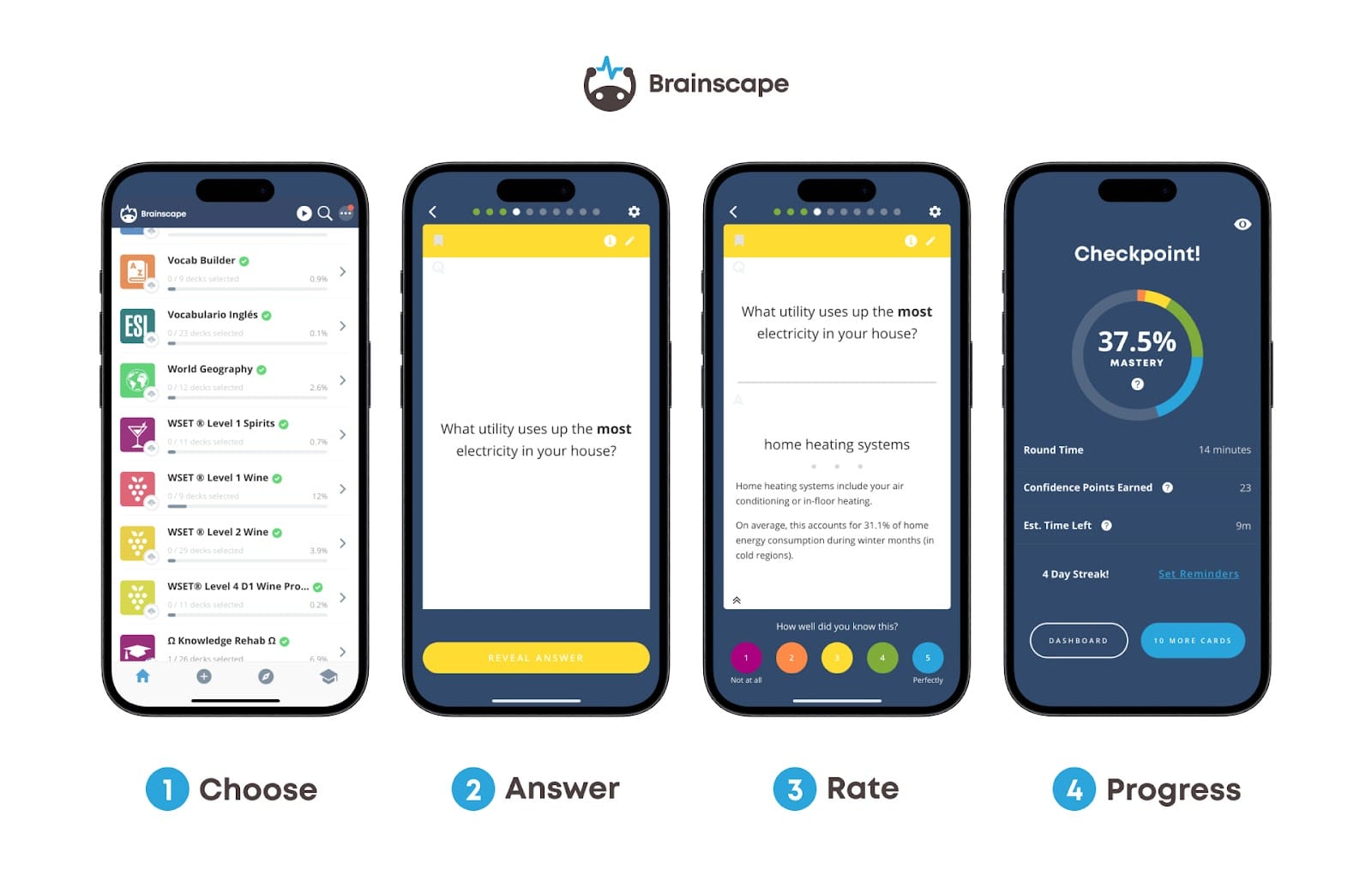

A great example of how active recall can be used in software is Brainscape, the world's best online flashcard learning platform. It uses active recall to yield greater benefits with limited study time. We do this by showing one question at a time on the front of a flashcard. Students are then asked to remember the answer before turning the card over without any hints. The active recalling of information deepens the cognitive pathways to the information.

Our system also ensures that learners are making a genuine active attempt to think of the answer by asking users to rate their confidence in each flashcard (on a scale of 1-5) before proceeding to the next one. Learners tend to keep their confidence ratings honest since they want our system of confidence-based repetition to help them optimize their study time.

Plus, students no longer need to agonize over what to study: Brainscape's algorithm selects the cards right in their zone of proximal development, removing the guesswork and freeing their minds to focus on learning rather than organization.

Whether learners are choosing from Brainscape’s huge library of flashcards, making their own flashcards, or using our AI toolkit to turn study notes into flashcards within minutes, using active recall (rather than multiple-choice self-tests) is a key strategy for deeply learning and retaining knowledge.

FAQ: Why Multiple-Choice Self-Tests Are Ineffective for Studying

What are the disadvantages of multiple-choice tests?

Multiple-choice tests often encourage surface-level learning. They test recognition rather than recall, meaning students might guess the right answer without truly understanding the material. They can also place an unhelpful emphasis on test-taking tricks over deep comprehension.

Why do I struggle with multiple-choice tests?

You might struggle because these tests can be tricky by design. Test writers use distractors that seem correct or that require subtle distinctions. If you haven’t mastered the material at a deeper level, guessing or overthinking can work against you. Strengthening active recall through flashcards can help prepare you more effectively.

What makes the multiple-choice type of test poor?

Its main weakness is that it doesn’t always measure what students truly know. It favors test-savvy students, rewards recognition over understanding, and doesn't reflect how we apply knowledge in real-life situations.

Use Brainscape to Promote Active Studying

How can you best help students to study actively rather than passively? Adaptive flashcard engines such as Brainscape are designed for the production of active study. They require the user to recall the target rather than simply recognizing it from multiple choices.

Active recall, together with spaced repetition and metacognition, is part of the foundational principles that transform Brainscape's flashcards into the ideal tool to improve your students' learning experience and make learning more efficient.

Get Brainscape's Educator User Guide

Curious to learn more about how to introduce Brainscape into your physical or virtual classroom? Our Educator User Guide provides a detailed walkthrough of how to get set up. It'll also give you all the material you need to motivate for its adoption amongst your students, their parents, and/or the faculty of your school or college:

Additional Reading

- The psychology behind multiple-choice exams

- The 20 best test-taking strategies used by top students

- How to Start Studying for a Test (Even When You Have Zero Motivation)

Sources

Biggs, J. (1979). Individual differences in study processes and the quality of learning outcomes. Higher Education, 8(4), 381-394. www.jstor.org/stable/3446151

Karpicke, J., & Roediger, H. (2006). Repeated retrieval during learning is the key to long-term retention. Journal of Memory and Language, 57(2), 151-162. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jml.2006.09.004

Pashler, H., Bain, P., Bottge, B., Graesser, A., Koedinger, K., McDaniel, M., & Metcalfe, J. (2007). Organizing instruction and study to improve student learning. Institute for Educational Sciences practice guide, U.S. Department of Education.