You've probably heard of learning styles—those quizzes that label students as auditory, visual, or kinesthetic learners. Teachers are encouraged to mix up activities to reach every type.

But is there real science behind this?

Let’s explore what learning styles claim to be, whether they actually matter, and what this means for your teaching.

The Learning Styles Hypothesis

The learning styles myth suggests that students each have a preferred way of learning—auditory, visual, or kinesthetic—and that tailoring instruction to these preferences leads to better outcomes.

The problem? These classifications are usually based on self-reported preferences from informal quizzes, not actual evidence of improved learning. Just because a student likes a certain way of learning doesn’t mean it’s the most effective for them.

Here are the three most commonly cited learning styles:

- Auditory learners are said to learn best through sound. Teachers are encouraged to use spoken explanations, verbal instructions, or audio-based activities.

- Visual learners absorb information better through visuals. Teachers should use diagrams, charts, or written instructions.

- Kinesthetic learners are thought to retain information best through movement and hands-on activities, like experiments or role-playing.

Are Learning Styles a Myth?

This sounds so neat and simple, right? A few neat boxes to target for Universal Design for Learning?

But there actually isn't much research to support it (criticisms of a lack of supporting research go as far back as 1980). Instead, most research calls into question the idea that the learning style preferences of students really matter for their learning. I've dug into the research, which suggests that not only is there little evidence supporting learning styles theory, but that there is just as much—if not more—against the effectiveness of learning styles targeting as there is in favor of it.

Just like many urban legends, learning styles are an idea that refuses to die.

Of course, there are a ton of theories about different learning styles that are not based on perceptions—as many as 71 different models. A discussion of all of them is too much to tackle and isn't what I want to do here.

What I do want to do is give you, the teacher, the best reasons why you shouldn't worry too much about learning styles—and what you should focus on instead.

1. Learning Styles Don't Make Learning More Effective

The main case against learning styles theory is that students’ supposed “preferences” don’t actually translate to gains in learning effectiveness.

According to Coffield et al (p. 35), “There is simply no evidence that the model is either a desirable basis for learning or the best use of investment, teacher time, initial teacher education and professional development.”

While it is natural for some students to claim that they prefer learning something through watching a video or playing a game, that does not necessarily mean they will learn better through that medium. Playing educational games may be a poor use of learning time, despite the potential gains in motivation that games may offer.

2. For Many Subjects, One "Style" May Be Best for Everyone

The literature often shows just one empirically “best” way to learn something, rendering learning styles moot. For example, the best way to learn computer skills is to try the steps yourself with a keyboard and mouse rather than just being shown or told! (i.e. Anyone would declare themselves a “hands-on learner” when it comes to computers, guitars, or tennis serves.)

Administering a general preferences survey like the Learning Styles Inventory is, therefore, more likely to uncover what students prefer to learn (e.g. computers vs. history vs. math) rather than how they like to learn them. It would be counterproductive to take someone’s preference for “writing things down” and use that as a way to teach them Excel or Photoshop.

3. Accommodating Preferences May Not Always Be Useful

We should also be careful not to pander exclusively to students’ learning preferences, as we need to foster their capacity to absorb information from a variety of media. Students need to learn how to handle a variety of information pathways in order to be adaptable to new learning environments.

4. Multimodal Learning is the Most Effective And Accessible

The benefit of thinking about learning styles in a classroom context is that it prompts educators to consider activities that use a variety of delivery methods. This is a good thing—but not necessarily because students have different learning styles.

Instead, it's a good thing because we know that multimodal learning is more effective than any single learning method. Presenting information visually as well as aurally is much more effective than either of them by themselves. If an educator can further enrich the learning with a hands-on project, so much the better.

Following the principles of Universal Design for Learning means designing multiple means of engagement, representation, and action, both exposing learners to a variety of means and giving them agency in how they interact with them.

5. Learning Styles Take Us Away From Other Effective Strategies for Teaching

The myth of learning styles obscures what we know about what really is effective ways to teach and learn.

For example, hundreds of studies have shown us that repetition of information is effective for remembering information after it's taught in the class. Spaced repetition—where repetition is done at intervals of varying length depending on how well the students have mastered the material—is particularly effective.

We also know that active recall is a more effective study strategy than simple passive re-reading or recognition. We're very clear that metacognition is one of the most important skills that we can teach students to make their learning more effective.

Each of these is supported by decades worth of cognitive science literature—they're much more important in terms of how students learn than students' preferences for auditory stimuli as opposed to visual stimuli. If we focus on learning styles, we risk forgetting the proven core of cognitive science.

FAQ: Why Learning Styles May Not Matter

What does it mean that the theory of learning styles has been debunked?

It means that despite its popularity, research has not found credible evidence that tailoring teaching methods to individual “learning styles” improves learning outcomes. Preferences may exist, but they don’t predict actual performance or effectiveness.

What happens when learning styles do not match with teaching styles?

Interestingly, nothing dramatic, because learning style mismatches aren’t strongly linked to poor outcomes. In fact, exposing students to a range of learning methods can make them more adaptable and improve their ability to engage with different types of content.

What are learning styles, and why are they important?

“Learning styles” refer to the idea that people learn best through specific modalities (e.g., visual, auditory, kinesthetic). While the concept is appealing, it's not strongly supported by evidence. A better focus is on strategies proven to help all learners—like active recall and spaced repetition.

Is VARK learning style a theory?

Yes, VARK is one of many learning style models. It categorizes learners as Visual, Auditory, Reading/Writing, or Kinesthetic. But like other models, it lacks scientific validation and should be approached more as a tool for student reflection than as a foundation for instructional design.

The Takeaway: Recalibrate Towards What We Know is Important in Learning

So what do you do as a teacher from all this? Build in activities that we know are good for everyone's learning. All students benefit from multimodal learning environments.

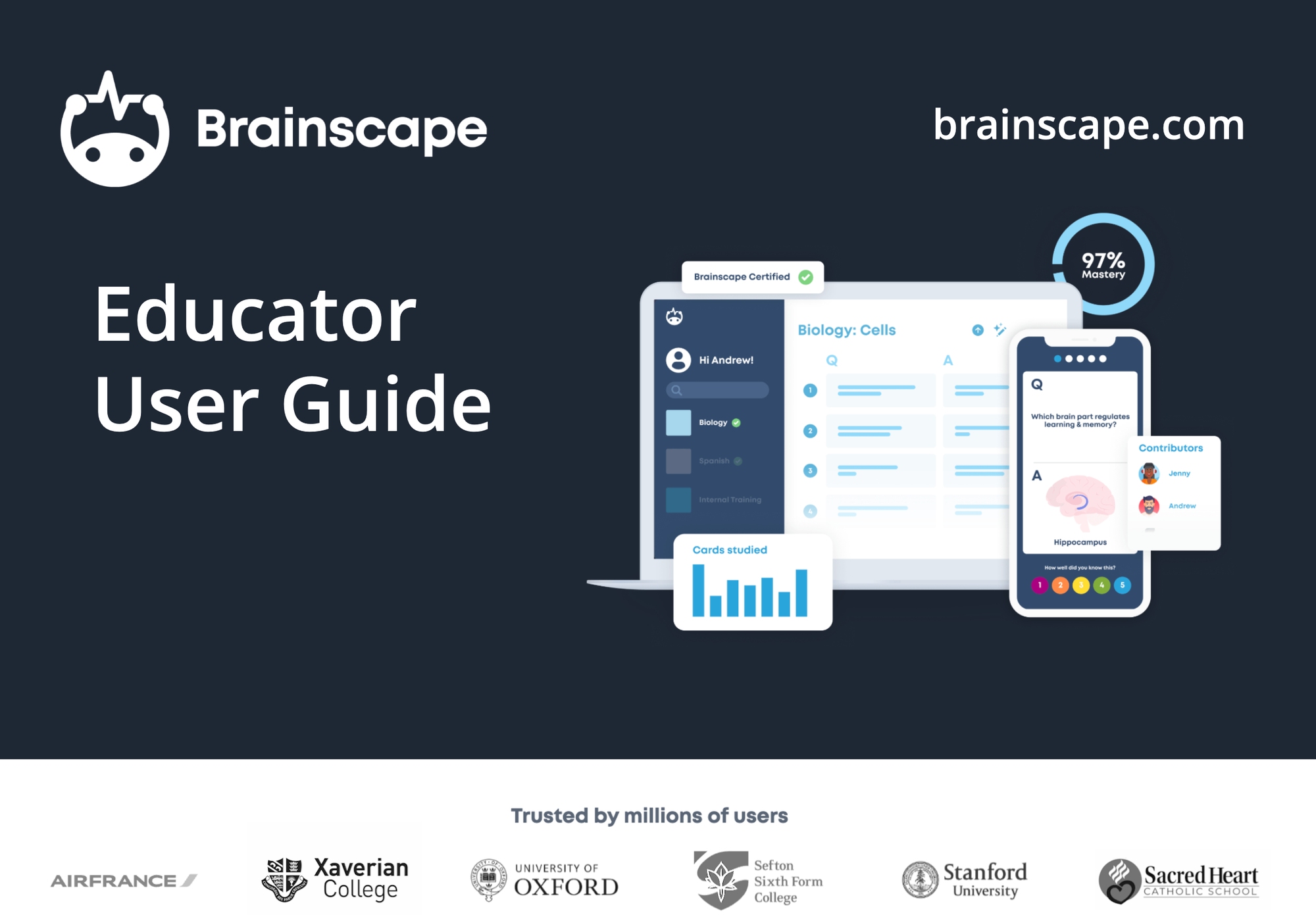

Speaking of evidence-based learning strategies, Brainscape is a digital flashcard platform designed on principles of cognitive science and the psychology of learning, so we know it works—and it'll work for all students, not just those with a particular learning style.

It takes the guesswork out of studying by allowing users to simply open the app and look at concepts in their zone of proximal development. By removing the task of deciding what to study, it frees mental energy for learning and makes learners more likely to study.

By taking the approach of creating evidence-based learning environments and lessons that are effective for everyone, we enable learning for everyone. No matter your learning style, you will improve your memory retention with Brainscape.

Get Brainscape's Educator User Guide

Curious to learn more about how to introduce Brainscape into your physical or virtual classroom? Our Educator User Guide provides a detailed walkthrough of how to get set up. It'll also give you all the material you need to motivate for its adoption amongst your students, their parents, and/or the faculty of your school or college:

Additional Reading

- The Secret to Learning More While Studying Less: Adaptive Learning

- Learn Deliberately to Learn Faster

- How we learn: the secret to all learning & human development

Sources

Cassidy, S. (2004). Learning styles: An overview of theories, models, and measures. Educational Psychology, 24(4), 419-444. https://doi.org/10.1080/0144341042000228834

Coffield, F., Moseley, D., Hall, E., Ecclestone, K., Coffield, F., Moseley, D., ... & Ecclestone, K. (2004). Learning styles and pedagogy in post-16 learning: A systematic and critical review. London, England: Learning & Skills Research Centre. https://www.voced.edu.au/content/ngv%3A13692

Coffield, F. (2008). Just suppose teaching and learning became the first priority. LSN Learning. London.

Freedman, R. D., & Stumpf, S. A. (1980). Learning style theory: Less than meets the eye. Academy of Management Review, 5(3), 445-447. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.1980.4288873

Job, V., Dweck, C. S., & Walton, G. M. (2010). Ego depletion—Is it all in your head? Implicit theories about willpower affect self-regulation. Psychological Science, 21(11), 1686-1693.

Magana, A. J., Serrano, M. I., & Rebello, N. S. (2019). A sequenced multimodal learning approach to support students' development of conceptual learning. Journal of Computer Assisted Learning, 35(4), 516-528. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcal.12356

McLeod, S. (2024) Vygotsky’s zone of proximal development, Simply Psychology - Vygotsky’s Zone Of Proximal Development. Available at: https://www.simplypsychology.org/zone-of-proximal-development.html

Odendaal, A. (2019). Individual differences between the practising behaviours of six pianists: A challenge to Perceptual Learning Style theory. Research Studies in Music Education, 41(3), 368-383. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F1321103X18774365

Orbell, S., & Verplanken, B. (2010). The automatic component of habit in health behavior: Habit as cue-contingent automaticity. Health Psychology, 29(4), 374.

Rohrer, D., & Pashler, H. (2012). Learning Styles: Where's the Evidence? Medical Education, 46(7), 634-635. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED535732

Romanelli, F., Bird, E., & Ryan, M. (2009). Learning styles: a review of theory, application, and best practices. American Journal of Pharmaceutical Education, 73(1). https://dx.doi.org/10.5688%2Faj730109