This article is part of Brainscape's Science of Studying series.

Picture this: You’re staring down your exam paper, pen in hand, heart thudding like a tiny drum solo, and your brain suddenly goes... blank. You know you studied this. You can even visualize the exact page in your notes, but the words just won’t come. It’s happened to me. And I know it’s happened to you, too.

That, my friend, is the tragic fate of passive studying: when you’ve read, reread, highlighted, summarized, and maybe even whispered sweet nothings to your textbook, but you never actually practiced remembering the information.

Active recall is the antidote. It’s the process of pulling knowledge out of your brain from scratch, without any memory crutches. When you ask yourself, “What are the phases of mitosis?” and you mentally wrestle the answer out of your gray matter before checking your notes… that’s active recall.

It’s not glamorous. It’s not “aesthetic studying” for TikTok. But it’s how your brain actually learns.

And because active recall is a core tenet of effective learning—and I’m obsessed with learning—I went on a deep dive to unearth the cognitive science behind it and the digital tools you can use to harness it, whether it’s for your own learning or that of your kids or classroom.

Let’s dive in!

What is the Active Recall Study Technique?

Active recall studying is when you actively stimulate your memory for a piece of information, without seeing the answer like you would by simply re-reading text or choosing from a list of multiple choices. For example:

- Who was the first president of the United States?

- What is the capital of Argentina?

- Where in the body is the basal ganglia located?

As I ask you each of these questions, your brain runs a lightning-quick search of its memory banks for the answers. It's performing this action "from scratch" with just the question as a prompt. (This is exactly what flashcards do and why I’m such a huge fan of using them to study for tests and exams. More on that in a bit.)

(Answers: George Washington, Buenos Aires, and the brain.)

This is active recall, a much more powerful way to teach your brain to remember than passive study techniques like reading and highlighting text.

Every time you retrieve a piece of information, the neural pathway connecting a question to an answer grows stronger and faster. Neuroscientists call this consolidation: each retrieval deepens the groove in your brain, like tracing a pencil line again and again until it’s carved into the page.

It’s a workout. The harder your brain strains to recall something, the stronger the memory becomes. (Psychologists lovingly call these “desirable difficulties.”)

So yes, when studying feels a little painful, that’s your neurons getting swole.

What’s the Difference Between Active Recall and Recognition?

Recognition is when you see an answer and think, “Oh yeah, I know that.”Active recall is when you have to produce the answer on your own.

Here’s an example:

- Recognition: A question reads “Who wrote Hamlet?” and gives you a list of multiple-choice answers. You scan it, see “Shakespeare”, think “that sounds right!” and click or check that option. You only recognized the correct answer on a list of possible answers.

- Active recall: Same question: “Who wrote Hamlet?” but this time there is no list of multiple-choice answers to scan; just a blank space for you to write your answer in. Now you have to pull “Shakespeare” from memory, which establishes a stronger neural pathway to that piece of information.

Recognition tricks your brain into overconfidence. Active recall exposes what you actually know and forces your brain to do the work that leads to real learning.

If that contrast still feels fuzzy in practice, it helps to see it laid out in plain categories. The infographic below maps common passive habits against the active strategies that build long-term memory.

How to Practice Active Recall

1.The “Read, Recite, Review” Mini-Cycle

- Read a short chunk of material.

- Close the book.

- Recite everything you remember out loud, on paper, to your cat, whatever works.

- Then review the original and see what you missed.

You’ll feel clumsy at first. That’s fine. The magic lies in the discomfort.

2. The Feynman Technique

- Pretend you’re teaching the topic to a sixth-grader (pets and houseplants also serve as captive audiences). This is a tactic called the Feynman Technique.

- If you struggle to explain something in simple terms, in a way that a sixth-grader would understand, then you’ve just discovered a weakness in your understanding. Go back, fix it, and re-explain until it clicks.

- If you can't explain it simply, you don't understand it well enough. (That’s what Einstein said and he was one smart dude.)

3. Quiz Yourself Like It’s a Game Show

- Create a list of short questions: tiny, bite-sized prompts that inspire lectures on the subject you’re learning about. (You can even turn them into flashcards. More on that in a second.)

- Every day, pick a few and test yourself without looking.

Example:

“Name the cranial nerves in order.”

“What’s the difference between meiosis I and II?”

“Explain the pathophysiology of asthma in 30 seconds.”

Obviously the exact questions will depend on the content but you get the point, right? You’re not just defining single facts but the intricate relationships and context between them.

It’s not glamorous, but it works.

4. Interleave and Shuffle

- Don’t spend massive blocks of time on a singular subject. Instead, test yourself concurrently on several subjects to mix it up and keep your brain working hard.

- For example, don’t answer 50 anatomy questions in a row. Mix it up with questions on pharmacology and pathology, if you happen to be studying medicine.

- This is called interleaving practice and is yet another strategy for optimizing your learning efficiency. Your brain will learn to switch gears, making you better at recognizing which knowledge to grab in an exam situation.

Now let’s talk about digital flashcards, because (1) by their very design they leverage the learning power of active recall and (2) paper flashcards are so last century. In other words, if you’re looking for a tool that’ll help you learn your subject quickly, flashcards are where it’s at!

Why Digital Flashcards Are the Best Active Recall Tool

Flashcards are the purest form of active recall: one question, one answer, no cheating.

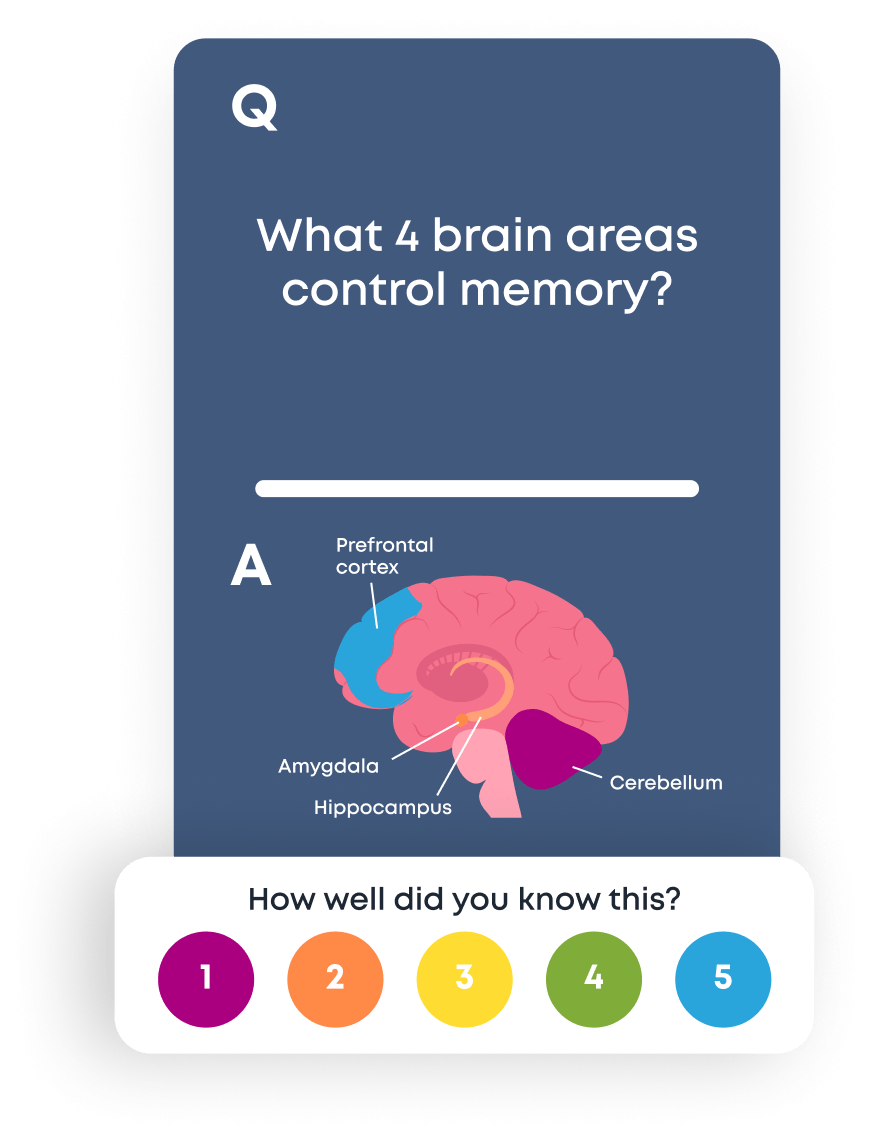

Sure, you can use paper flashcards if you’re a sucker for punishment, but digital flashcard apps like Brainscape (pictured above), Anki, and Memrise are just way better.

Here’s why:

- Flashcards reframe knowledge as questions, which compel you to actively recall the answer from scratch. This, as I’ve spent the first half of this article explaining, leads to deeper and faster learning.

- They’re always with you. Waiting in line? On the bus? Between lectures? Whip out your mobile device and test yourself.

- They space your reviews perfectly. Algorithms automatically show you your weakest concepts more often, and strong ones less often. (Look for the term “spaced repetition” when shopping around for a good flashcard app. That’s where the secret sauce lies.)

- They let you track your confidence. When you rate how well you know a card, you’re practicing another powerful memory tactic called metacognition (thinking about your thinking). This further deepens learning.

- They’re clean and focused. One prompt, one answer, no distractions. Also, prompts can range in complexity from the simple, single-definition prompt (“What is Rayleigh scattering?”) to a complex prompt that encourages you to recall a detailed network of concepts (“What series and combination of atmospheric factors lead to the formation of supercell thunderstorms?”)

Remember this last point. Flashcards aren’t just for vocabulary or trivia. They work for formulas, anatomy, case scenarios, even essay outlines. If the information can be asked, it can be “flashcardized”. (I made that word up but point made, right?)

So, while everyone else is reading and rereading their notes, and hoping their brain “plays nice”, you’re running mental drills that literally change your brain.

So, What’s the Takeaway on Active Recall?

If you want to study more efficiently (or help your students learn more efficiently):

- Stop rereading. Start retrieving.

- Ask questions. Don’t prompt the answers.

- Make discomfort your guide.

- Test yourself every day, even in tiny doses.

- And use digital flashcards to keep reviews consistent, spaced, and honest.

Because learning isn’t about feeling prepared, it’s about being able to prove it when it counts.

Additional Reading

Don’t stop here! Keep nerding out over how your brain actually works with these awesome reads:

- What is Metacognition (& How Can It Help You Remember Anything Better)?

- What is Spaced Repetition (& Why Is It Key To All Learning)?

- What is Retrieval Practice (& Why Is It Key To Successful Studying)?

References

Agarwal, P. K., Nunes, L. D., & Blunt, J. R. (2021). Retrieval practice consistently benefits student learning in real-world classrooms: A review of applied research. Educational Psychology Review, 33(2), 1–30. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-020-09535-9

de Bruin, A. B. H., & van Merriënboer, J. J. G. (2023). Worth the effort: Start and stick to desirable difficulties to improve learning. Educational Psychology Review, 35, 72. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-023-09766-w

Karpicke, J. D., & Blunt, J. R. (2011). Retrieval practice produces more learning than elaborative studying with concept mapping. Science, 331(6018), 772–775. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1199327

Roediger, H. L., & Karpicke, J. D. (2006). Test-enhanced learning: Taking memory tests improves long-term retention. Psychological Science, 17(3), 249–255. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9280.2006.01693.x

Trumble, E., Kuhr, B., & Rawson, K. A. (2023). A systematic review of distributed practice and retrieval practice in education. Education Sciences, 13(7), 688. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci13070688

Zheng, Y., Martorella, G. A., & Shanks, D. R. (2024). A working-memory-dependent dual-process model of the testing effect. npj Science of Learning, 9, 11. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41539-024-00268-0