Growing up, I went to a K-12 school that required foreign language classes for all grade levels. The only problem was that at the time, the elementary school only offered Spanish classes, and at least half of the school’s population consisted of native speakers—many of whom were from South America.

The school later introduced French classes, as well as Spanish classes for native speakers, but I distinctly remember taking several years of Spanish classes alongside my friends from Colombia and Venezuela. The problem is that even native speakers make grammar mistakes ... and aren't necessarily masters of their own languages.

Grammar mistakes and language rules

You might be thinking that the problem was that these students already knew all of the course material. In fact, those of us who were beginners hoped that this was the case, and often begged our South American friends for help with the homework. But the funny thing is, they often had quite a bit of trouble with the material. Of course they knew how to translate all of the basic vocabulary, although sometimes they gawked at some of the words that we had to learn, insisting that these were never used in everyday conversation.

The real problem for them, however, was grammar.

Don’t get me wrong, these kids were 100% fluent and spoke to each other perfectly in Spanish, just as you’d expect from native speakers. But when asked to conjugate a specific verb in the imperfect tense, for instance, these students did not excel as much as you might think. If anything, they had more trouble than those of us who were learning the language from scratch. What’s the deal with that?!

We at Brainscape have spent years creating the best foreign language study app out there. And while working with experts and diving into the brain science behind learning a language faster, we found that some language learning methods for learning grammar (and vocab) are better than others. It's why we can:

- help you learn a language faster, and

- help answer questions like why foreigners are, perhaps, better at grammar than native speakers.

Without further ado, let's dive into it!

Why is grammar so hard for native speakers?

One reason is that this kind of language instruction comes off as unnatural for people who are already proficient. After all, when I learned English as a baby, no one asked me to practice conjugating any verbs—or practice anything, for that matter. It was all about exposure and everyday usage, not explicit instruction. I had never even heard of “preterite” or “imperfect” until taking foreign language classes.

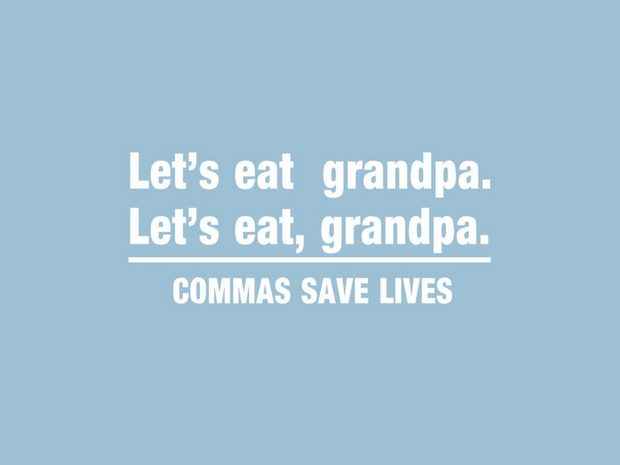

Of course, I did have some English grammar instruction later on in middle school, but I can’t say I remember much of what came out of those classes. How many native English speakers do you think know what a “gerund” is? And I can think of a few errors on the part of a certain former U.S. President that involved far more basic grammar than that. (Sorry, I had to.)

Natural learning vs. school instruction

Unlike native speakers, foreign language learners usually learn the explicit grammatical rules of the target language very early on. I know that any regular “-ar” verb in Spanish (e.g., caminar or “to walk”) will be conjugated as “-aba,” “-abas,” and so on in the imperfect, and I know that because my Spanish teachers reinforced this to us every year until we had reached conversational proficiency.

My South American friends, on the other hand, probably picked these things up more naturally, and therefore learned to use them in everyday conversation—without ever learning the “rule.” I certainly don’t recall anyone ever teaching me the phrase “used to” as an imperfect verb form in English (e.g., “I used to live in Boston”), but I use the phrase all the time without thinking twice about it.

On a related note, I found an interesting blog post that discusses a study that found that postgraduate students performed far better than high school dropouts on an English grammar tests—both groups being native English speakers. Of course, there are a number of potential confounds in a study like this, but this is still an interesting finding considering I certainly never had any English grammar instruction after high school, and I doubt the postgraduates in this study did either. In general, this disparity challenges linguist Noam Chomsky’s theory of a universal grammar by suggesting that being a native speaker does not mean that you’re a master of your own grammar.

I think there is a lot of potential for some interesting future research in this area, specifically comparing the grammar abilities of native speakers versus non-native speakers of a given language. This post was largely speculative and based on my own experiences and those of my peers, but I think there could be a lot of truth to these ideas.

Don't worry too much about perfect grammar in the beginning

What does this all mean? Basically, don't worry too much about learning perfect grammar when you're just starting a language. Sure, eventually you want to get to a place where you're not making a ton of mistakes. But save that for later. At the beginning, just focus on learning vocabulary, basic verbs, and how to make sentences). Then start using the language to communicate. You'll make some mistakes, but that's okay. Many native speakers might not know the grammar either.

If you’re interested in learning the grammar or vocabulary of any language, check out Brainscape's foreign language flashcards. And if you're really on a serious language learning journey, check out our comprehensive guide to learning any language more efficiently.

References

Dupre, G. (2024). Acquiring a language vs. inducing a grammar. Cognition, 247, 105771. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cognition.2024.105771

Nagel, D. (2024, August 5). You don’t need to study grammar to learn a foreign language. The Mezzofanti Guild. https://www.mezzoguild.com/you-dont-need-to-study-grammar-to-learn-a-foreign-language/

Saldivar, M. G. (2010, July 8). New study finds some native speakers may not grasp their language’s basic grammar. Cognitive Science Blog. https://cogsciblog.wordpress.com/2010/07/07/new-study-finds-some-native-speakers-may-not-grasp-their-languages-basic-grammar/

The University of Arizona. (2024). About Noam Chomsky. College of Social & Behavioral Sciences. https://sbs.arizona.edu/chomsky/about

Zhang, J. (2009). Necessity of grammar teaching. In International Education Studies: Vol. Vol. 2 (Issue No. 2, pp. 184–185). https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1065690.pdf