You have your textbooks ready, a line of Red Bull cans ready to pop, and your phone is hidden in another room. The curtains are drawn like a 1960s spy movie, and you’re trying to ignore the sudden urge to take a nap. It’s time to study.

The only problem is that you might be making a huge common study error that most students commit: You might be studying too "passively".

The difference between active studying and passive studying can be as big as the difference between (a) lifting heavy weights at the boundaries of your abilities versus (b) mindlessly lifting 1-pound mini-weights while staring at your phone. If your goal is to build muscle (or build knowledge), the best way to achieve it is to do heavy weightlifting!

We’re here to show you how to stop making this classic mistake and, instead, engage in active studying, which will empower you to learn quicker, more efficiently, and in a way that ensures that the knowledge sticks!

But before we reveal the solution, let’s identify the mistake that so many students make in their approach to preparing for tests and exams ...

The Folly of Passive Studying

The reason most students make the mistake of studying passively is that we aren’t taught HOW to study when we hit the fateful grade where educators start firing tests, quizzes, and exams at us like academic missiles.

I remember preparing for my first-ever exam. I was in 7th-grade biology class. I didn’t know quite what to do to memorize all the information, so I reread the chapter in the textbook, looked over my class worksheets several times, and called it a day.

I just didn’t know any better.

The mistake I made was to think that reading through the textbook and class notes was the correct study approach. What I was doing was studying passively. And because of it, I scored a measly 65% for my biology exam, which sucked enormously because it was my favorite subject.

Passive studying looks like this:

- Reading the textbook and notes once, maybe twice.

- Highlighting the odd sentence or phrase.

- Watching instructional videos.

- Getting sidetracked by funny videos of college kids doing dumb things,

Students tend to prefer passive studying because it's easier and more comfortable. In fact, this Harvard study shows that most students even convince themselves that passive methods are more effective and that lecturing professors provide "better learning" than professors who engage students in class projects, even though those hands-on projects ultimately provide much deeper education than traditional passive methods.

Passive studying makes you feel like you’re doing good work when you’re really not.

Active Studying to the Rescue!

The very best approach to learning information for an exam is to engage in active studying.

The thing about active studying is that it’s, well, active. It means you’re not simply going through the motions of reading information and trying to remember it. You’re engaging a lot more than just your reading ability.

Active studying means you’re becoming curious, you’re asking yourself questions, and you’re putting your brain into a different mode in order to truly learn the new material. When you do this, you’re treating the information as something valuable that you can use to solve a problem. This, in turn, activates the problem-solving parts of your brain, meaning you’re much more likely to retain what you’ve learned, and you're most likely to be using your study time effectively overall.

Here are some super useful techniques you can use for active studying:

Tip 1: Answer Questions on the Material

At the end of most textbook chapters, you’ll find a series of questions on the information in that chapter. You can also do past exams and tests. Read through the questions and answer them, without looking back through the textbook until you've already formulated your own answer. This engages your powers of active recall, a much more effective way to cement things in your memory.

Unlike selecting an answer from a multiple-choice list (which doesn’t work), active recall forces your brain to retrieve the information from your memory. Like working out a muscle, this makes a stronger memory trace, making that information easier to remember in the future.

It’s also worth noting that the textbook questions we’re recommending you practice on are sometimes recycled by professors for exams, so studying them now is a good move!

If your textbook doesn’t have questions, even better. Craft your own questions! This uses metacognition (thinking about your thinking) and forces you to analyze what was most important about the chapter you’ve just read.

Tip 2: Take Notes

Reading and re-reading your notes and textbook is only the first step of studying. You should then take notes of the most important points, summarizing and paraphrasing what you've (re)read.

This compels you to simplify and synthesize the information in a way that makes more sense to you and is easier to review later. The action of crafting notes also gives your brain much greater traction on the subject material, since you aren’t merely glancing over it but are actively engaging with it.

This brings me to an even better way to take notes ...

Tip 3: Make Flashcards

Flashcards are an extremely efficient way to learn new material because they break down mountains of information into succulent little bite-sized question-and-answer pairs. This makes learning far more manageable.

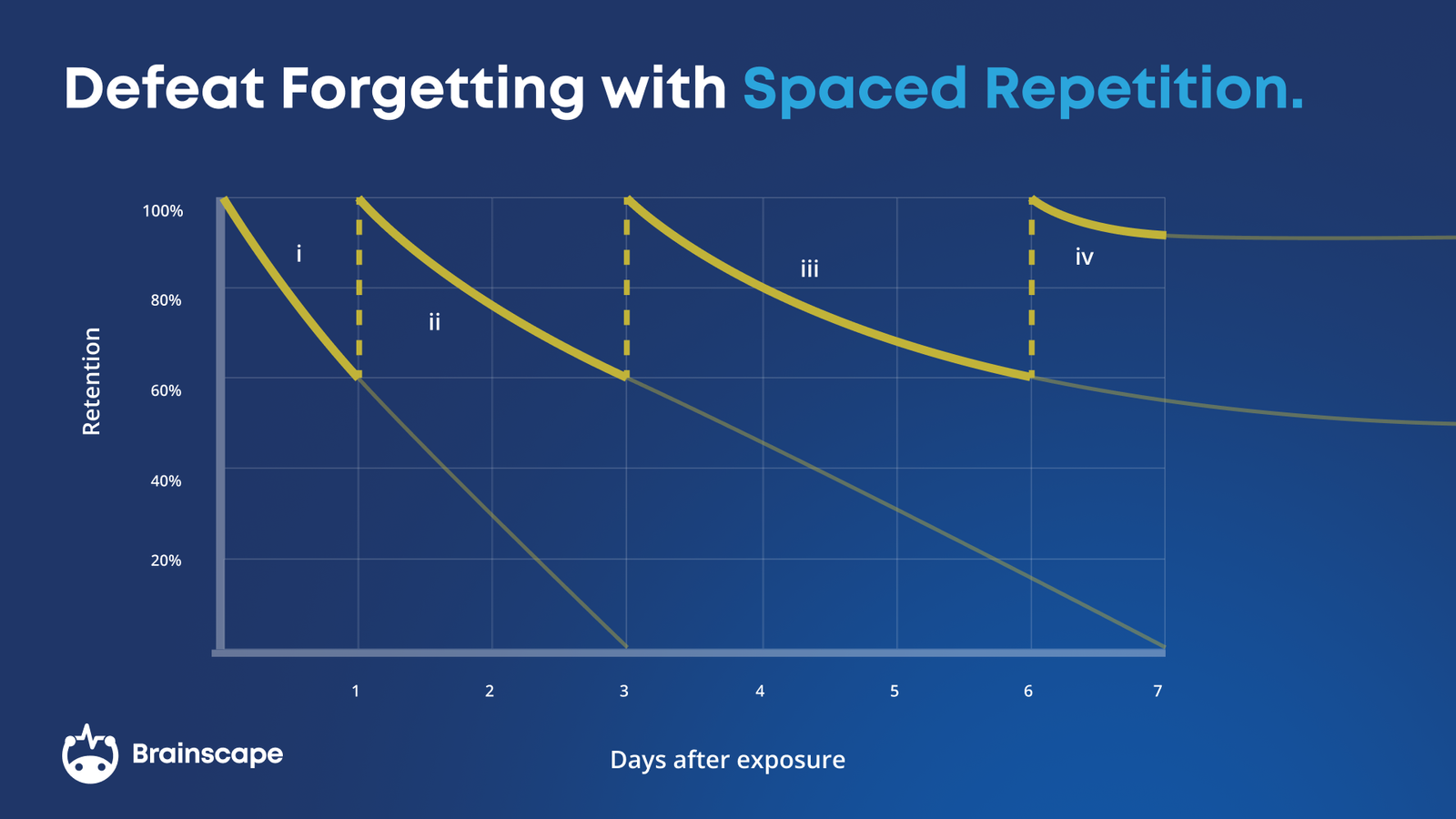

Plus, as you progress through the material, you can set aside the flashcards you find easy and instead concentrate more on the difficult ones. Using flashcards with spaced repetition will help you permanently onboard all the facts.

CREATING flashcards (rather than just using them) also compels you to reframe the information into bite-sized parcels, which is a valuable learning exercise in itself.

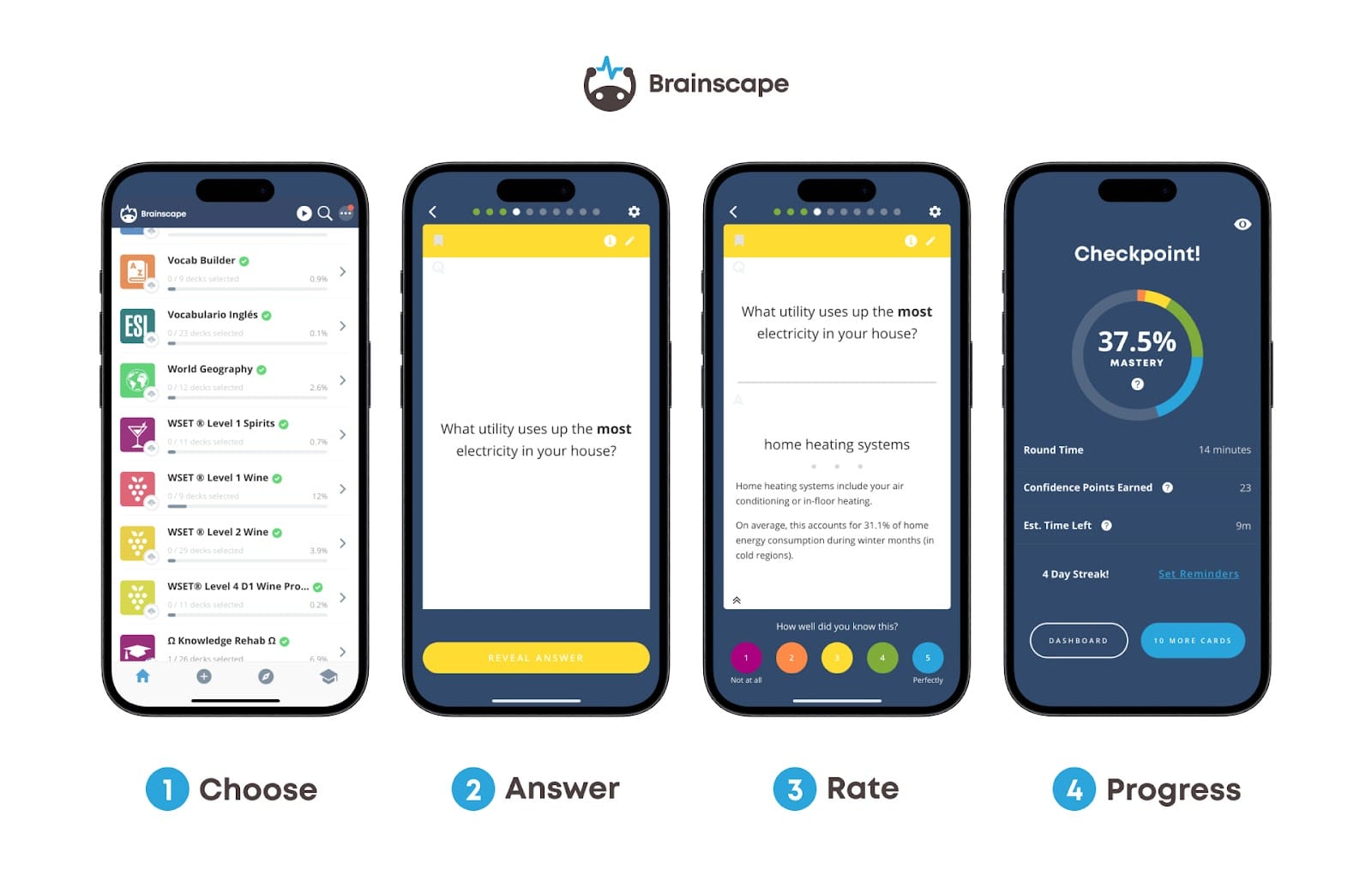

Brainscape takes all of this to the next level with its sophisticated learning algorithm. The Brainscape app automates the spaced repetition we mentioned above to make your learning hyper-efficient: repeating information at optimal intervals so you get just the right number of exposures to commit new facts to memory.

For the user, this means never having to think about when to study what. Just open the app and see if you remember the flashcard that's in front of you.

When you transform your study material into question-and-answer pairs to put on flashcards, you’re again using active recall. The Brainscape mobile app is an easy way to fit studying into time that would otherwise be wasted scrolling; for instance, when you’re on the bus or waiting for your partner to finish showering.

Tip 4: Lecture Yourself

Another way to engage in active studying is the Feynman Technique. This is a study method recommended by American theoretical physicist Richard Feynman, who found that the best way to remember information is to talk about the subject out loud and in the simplest terms, as though teaching a 5th grader.

The way you can do this very simply involves shutting your books and delivering a lecture to yourself (or an unsuspecting friend/neighbor/pizza delivery guy) about what you’re currently studying. This method of memory retrieval is called free recall. Unlike active "cued" recall, it requires your brain to retrieve information with no cues at all. Free recall is a way to fit your new knowledge into a framework that makes sense to you.

The Feynman Technique is a very effective way to deeply internalize what you’ve learned and make it your own. Also, to teach a subject, you've got to really know it. And in doing this, you'll not only consolidate what you've learned but you'll also identify any logical gaps in your understanding, which you can then address.

Other Obvious Studying Mistakes

Now that you know how to engage your powers of active (read: efficient and effective) study, let’s look at some other studying mistakes students make:

- Waiting until the last minute and cramming (it’s the #1 enemy of effective study).

- Not making regular studying a habit.

- Not taking good notes.

- Not optimizing your brain for the exam.

Acing your studies is largely a product of building good habits and doing the hard work early, so you get to enjoy the rewards later.

It’s Not Study, It’s Practice

Forget the word "studying", which we're conditioned to think of as "passively reviewing". Instead, think of studying as practicing.

Acquiring knowledge is a skill you can practice. To accelerate your learning, you have to actively engage your brain: make it do some work to earn its keep.

When you practice, you push yourself to make things uncomfortable but manageable, keeping yourself in the zone of proximal development, where you’re adding new knowledge at just the right rate to stretch your brain but not too much to be overwhelmed. (Brainscape does this for you automatically.)

On the other hand, passive studying is like learning to swim by reading an instruction manual. It doesn’t work.

The Result of Active Studying

Most things worth doing are hard. But if you make doing the hard stuff into a habit, you’ll be amazed at how things that were once a struggle become easy for you. That 12-lb weight you could once barely prize off the rack now feels like a feather.

All it takes is a few minutes of Brainscape flashcards a day. When active studying becomes your normal mode, come exam time, you’ll be so prepared that your aura of calm will elevate you above your anxiety-stricken peers.

Additional Reading

- How to Study Effectively: The Ultimate Guide

- How to Build Strong Study Habits

- How to Study While Exercising

References

Ang, K. C., Afzal, F., & Crawford, L. H. (2021). Transitioning from passive to active learning: Preparing future project leaders. Project Leadership and Society, 2, 100016. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.plas.2021.100016

Deslauriers, L., McCarty, L. S., Miller, K., Callaghan, K., & Kestin, G. (2019). Measuring actual learning versus feeling of learning in response to being actively engaged in the classroom. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 116(39), 19251–19257. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1821936116

Gauvain, M. (2020). Vygotsky’s Sociocultural Theory. In Elsevier eBooks (pp. 446–454). https://doi.org/10.1016/b978-0-12-809324-5.23569-4

Johns Hopkins University. (2024). Active Versus Passive Learning. Johns Hopkins University Academic Support. https://academicsupport.jhu.edu/resources/study-aids/active-versus-passive-learning/#:~:text=Passive%20learning%20is%20instructor%2Dcentered,chunks%20of%20information%20when%20reviewing.

Kang, S. H. K. (2016). Spaced repetition promotes efficient and effective learning. Policy Insights From the Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 3(1), 12–19. https://doi.org/10.1177/2372732215624708

Reyes, E., Blanco, R. M. F., Doroon, D. R., Limana, J. L., & Torcende, A. M. (2021). Feynman Technique as a heutagogical learning strategy for independent and remote learning. Recoletos Multidisciplinary Research Journal (Online)/Recoletos Multidisciplinary Research Journal (USJ-R. Print)., 9(2), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.32871/rmrj2109.02.06